Written for the Bob Marley Celebrations, February 2000

“My music will go on forever. Maybe it’s a fool say that, but when me know facts, me can say facts. My music will go on forever.” -The Honorable Robert Nesta Marley

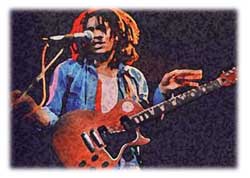

Revolutionary, visionary, musician, near prophet, father, messenger, son and the single most important influence on Reggae music, Bob Marley has taken on an iconic status worldwide. His image and his music appear in all corners of the earth, and he’s still moving people with his universal and timeless message. Despite the commercialization of Marley’s image since his death (a Universal Studios’ Bob Marley theme park opened last year in Orlando, Florida, Tuff Gong clothing is all the rage, Warner Brothers is releasing a Bob Marley biography starring Rohan Marley and Lauryn Hill, and as of press time, “Chant Down Babylon,” the tribute album featuring hip-hop artists, is #85 on the Billboard Top 200), Marley was a controversial and complex figure during his short life.

Born in a rural area of St. Ann’s Parish on February 6, 1945, to a young, black, Jamaican woman (Cedella Booker Marley) and a white British officer (Norval Marley), during a time in Jamaica when society divided strictly along racial lines, Marley had to come to terms with his own racial identity at an early age. In the video biography, “Time Will Tell,” Marley was asked whether he was prejudiced against white people. He replied, “I don’t have prejudice against myself. My father was a white and my mother was black. Them call me half-caste or whatever. Me don’t dip on nobody’s side. Me don’t dip on the black man’s side nor the white man’s side. Me dip on God’s side, the one who create me and cause me to come from black and white.” Perhaps it was his biracial background that led Marley to write songs with a universal message. One of his most profound songs addressing unification, “War,” took the words of a speech by Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia and put them to music, “Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally discredited and abandoned÷WAR!”

Growing up, Bob had little contact with his father and frequently moved around, living with aunts and friends all over the island. But in 1957, Cedella Booker, who was then living in Kingston, decided that her son should join her. The two lived in Trench Town, an area of Kingston named for the part of the city that was built over the ditch that drained the city’s sewage. There Bob met Neville “Bunny” Livingston (who became Bunny Wailer), the son of the man Cedella was dating at the time. Bob and Bunny would sit and groove to American radio, listening to popular R&B artists like Sam Cooke, Curtis Mayfield, Ray Charles, the Drifters and Fats Domino. Bob quit school and took a job as a welder, but his heart was in the music. He and Bunny would spend all of their free time together perfecting their vocals under Joe Higgs’ supervision. It was with Joe that they eventually met youngster Peter McIntosh (later shortened to Tosh). Although Bob had recorded “Judge Not” for Leslie Kong’s Beverley’s label in 1962, he decided a year later that performing with a group was the way to success. The three formed a vocal trio and named themselves the Wailers, after ghetto sufferers who had been born “wailing.”

In 1963, the Wailers signed to Clement “Sir Coxone” Dodd’s Studio One label, and released “Simmer Down,” which instantly became a number one hit. During the following two and a half years, they recorded over one hundred songs, and at one point in 1965 held five of the top ten slots on the Jamaican charts. The Wailers were practicing Rastafarians, so they had grown their dreadlocks and lived by the words of the Bible. In 1966, Bob married Rita Anderson, and moved to the United States where his mother was now living. But before the year was over, he moved back to Jamaica, where Rastafari was growing in popularity. Bob once said, “People want to listen to a message, word from Jah. This could be passed through me or anybody. I am not a leader. Messenger. The words of the songs, not the person, is what attracts people.”

In 1970, Aston “Familyman” Barrett (bass) and his brother Carlton (drums) joined the Wailers as Jamaica’s indisputably hardest rhythm section. The Wailers were a phenomenon in Jamaica, but they were virtually unheard of elsewhere. Soon the tides would change, and in 1972 the Wailers got their big break when Island Records’ president, Chris Blackwell, signed them. The resulting album, “Catch A Fire,” (with “Stir It Up” and Tosh’s “Stop That Train”) introduced Reggae to an international audience. The following album, “Burnin’” (1973) included newer versions of some of the older songs and showcased new songs, “Get Up Stand Up” and “I Shot the Sheriff,” which became a huge hit for Eric Clapton the following year in the United States.

The Wailers broke up soon after, leaving Bunny, Peter and Bob to pursue their own musical careers. The reasons for the break-up were never clear. Tosh claimed that Blackwell wanted Bob in front because of his fair skin color and others claimed that Bunny and Peter wanted to achieve their own success, apart from Bob. For whatever reason, the band was no longer together. Bob continued with the addition of the female I-Threes (Rita Marley, Judy Mowatt and Marcia Griffiths) and in 1975, Bob Marley and the reconstituted Wailers released “Natty Dread” which continued to embody an activist spirit and Marley’s faith in Rastafari. “Rastaman Vibration” came next and was the first album to crack the American charts. With tracks like “War,” “Crazy Baldhead,” “Who the Cap Fit” and “Johnny Was,” Marley’s voice was clear and ubiquitous.

On December 3, 1976, Marley was scheduled to perform a free “Smile Jamaica” concert, aimed at reducing tensions between warring political factions in the country. The evening before the show, Marley was attacked by gunmen, “It was a night I’n’I was rehearsing at 56 Hope Road, and cool out there, y’know. And then gunshot start to fire and t’ing, y’know. But after awhile we hear it was like some politically motivated type of t’ing. But it was a really good experience for I’n’I, y’know. Nobody died.“ Wounded but not killed, Marley still performed, shocking the 80,000 fans that had come out to see him that night. This launched his larger than life aura. Immediately after the show, he left Jamaica and went to London where he recorded “Exodus,” the album that established Marley as an international superstar. Released in May of 1977, it remained on the UK charts for 56 straight weeks.

Through all of his international success, Bob gained a reputation as a ladies’ man. He once admitted that women were his only vice, and he usually kept good company, whether it was the daughter of the President of Gabon or Miss World 1976. Although Rita was his wife and the mother of three of his children (Ziggy, Stephen and Cedella), Marley had a total of eleven children with seven different women. In fact, five of the children were born within seven years of his marriage to Rita (Robbie, Rohan, Karen, Ky-mani and Julian). Rita started to raise all of the children as an extended family, saying, “It is something you learn to live with over a period of time. I think Bob had such a lack of love when he was growing up. He seemed to be trying to prove to himself whether someone loved him and how much they loved him. There came a time when I had to say to him, ‘If that’s what you want, then I’ll have to learn to live with it.’ But there were certain things I would have to draw the line at.”

After “Exodus,” the band released “Kaya”in 1978. The album, a collection of love songs, was a change of pace for Marley. Bob commented on his reputation for writing activist lyrics, “You can’t show aggression all the while. To make music is a life that I have to live. Sometimes you have to fight with music. So it’s not just someone who studies and chats-it’s a whole development. Right now is a more militant time on earth, because it’s Jah Jah time. But me always militant, you know. Me too militant. That’s why me did things like ‘Kaya,’ to cool off the pace.” He added, “Maybe if I’d tried to make a heavier tune than ‘Kaya’ they would have tried to assassinate me because I would have come too hard. I have to know how to run my life, because that’s what I have, and nobody can tell me to put it on the line, you dig? I know when I am in danger and what to do to get out. I know when everything is cool and I know when I tremble, do you understand?”

Marley returned to Jamaica in April of 1978 to perform at the memorable “One Love Peace Concert” on the same bill as top performers Jacob Miller and Inner Circle, The Mighty Diamonds, Dennis Brown, Culture, Dillinger, Big Youth, Peter Tosh and Ras Michael and the Sons of Negus. While the political rivalries in Jamaica were vicious and the overall political climate was tense, Marley got up on stage and publicly united Prime Minister Michael Manley and leader of the opposition, Edward Seaga, by joining hands. “I just want to shake hands and show the people we’re gonna unite…we’re gonna unite…The moon is high over my head, and I give my love instead,” Bob declared.

The 1978 world tour took them to Japan, Australia and New Zealand. It was also Bob’s first trip to Africa where he visited Kenya and eventually Ethiopia, the spiritual home of Rastafari. Although Marley’s racial views were more encompassing than those of Tosh or other militant groups of the time, Marley’s views about world economics were quite fervent. In 1976, he told writer Timothy White, “We should all come together and create music and love, but is too much poverty. TOO MUCH POVERTY. People don’t get no time to feel and spend them intelligence. The most intelligent people are the poorest people. Yes, the thief them rich, pure robbers and thieves, rich! The intelligent and innocent are poor, are crumbled and get brutalized daily. Me don’t love fighting, but me don’t love wicked either… I guess I have a kinda war thing in me. But is better to die fighting for freedom than to be a prisoner all the days of your life.”

The “Survival” album, released in 1979, was a collection of pan-African solidarity songs, including “Africa Unite” and “Zimbabwe.” This album resulted in an invitation by the Government of Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) to headline their Independence Day celebration in 1980, which was the highest honor the band had ever received. Continuing on a European tour, Bob Marley and the Wailers broke festival records time and again. They drew 100,000 people in Milan and the album “Uprising,” which was released in May of 1980, hit all of the European charts.

The end was near for Marley as he had ignored severe health problems. During the 1977 European tour, Marley and the band challenged some French journalists to a pick-up soccer game where Marley injured his foot. Although treatment revealed the presence of cancerous cells, Marley refused surgery on several occasions. The cancer caught up with him in 1980 when he was on tour in New York and collapsed while jogging in Central Park. Doctors found that the cancer had spread to his brain, liver, and lungs. Bob died eight months later in Miami on May 11, 1981 at the age of 36.

Marley’s funeral was a national event in Jamaica as many fans and citizens lined the streets in mourning. A month before he passed, he was awarded Jamaica’s third highest honor– Jamaica’s Order of Merit–for his outstanding contribution to the country’s culture. He left his wife, Rita, his eleven children, a $30 million estate, an incredible body of music and a whole culture of devoted Reggae artists to follow in his footsteps. His body now rests at a mausoleum at Nine Miles in St. Ann’s Parish, but his music, his life, his activism, his search for the truth and his legacy will never be forgotten. As he once told biographer Stephen Davis, “I don’t have to suffer to be aware of suffering. So is not anger [I have], but truth, and truth have to bust out of man like a river.”

New Comments