‘Love is everything,’ he said, simply. ‘It is what created the world. It is what made you an’ me, child, brought us into this world.’

‘Love is everything,’ he said, simply. ‘It is what created the world. It is what made you an’ me, child, brought us into this world.’

And somehow the words didn’t sound banal, coming from him. He spoke with such simple directness that it seemed to give a new import to everything he said. It was as though the common words of everyday usage meant something more, coming from his lips, than they did in the casual giving and taking of change in conversation, the way it was with other folks.

— Roger Mais, Brother Man (27)

Among the many highlights of Calabash Literary Festival 2004 was the launch of the 50th anniversary edition of Roger Mais’ Brother Man, the first novel to depict a Rastafarian sympathetically. Calabash spearheaded the reissue in association with Macmillan-Caribbean, and the 184-page novel was read in its entirety Saturday evening by journalist-broadcaster Barbara Blake Hannah, actress Leonie Forbes, journalist-lecturer John Maxwell and Jamaica’s Minister of National Security Peter Phillips.

Brother Man is the memorable depiction of a Rasta protagonist named John Power, a shoemaker, healer and a visionary, and his story was set during a time when Rastas were pariahs of Jamaican life. It would not be, for instance, until several years later, in 1960, that the University of West Indies-Mona dispatched a team of professors to study the “sect,” which was feared and accused of being anti-Jamaican. Their “University Report” on the movement suggested things which took great time for the society to absorb, including the fact that Rastafarians were a complex and heterogeneous community, not just the stereotypes of ghetto thugs the bourgeoisie feared them to be. Mais already knew this, and he shows Power, better known as Brother Man (or, because the novel is sensitively attuned to speech, “Bra’ Man”), circulating peaceably in the community, amid the “chorus of people in the lane.”

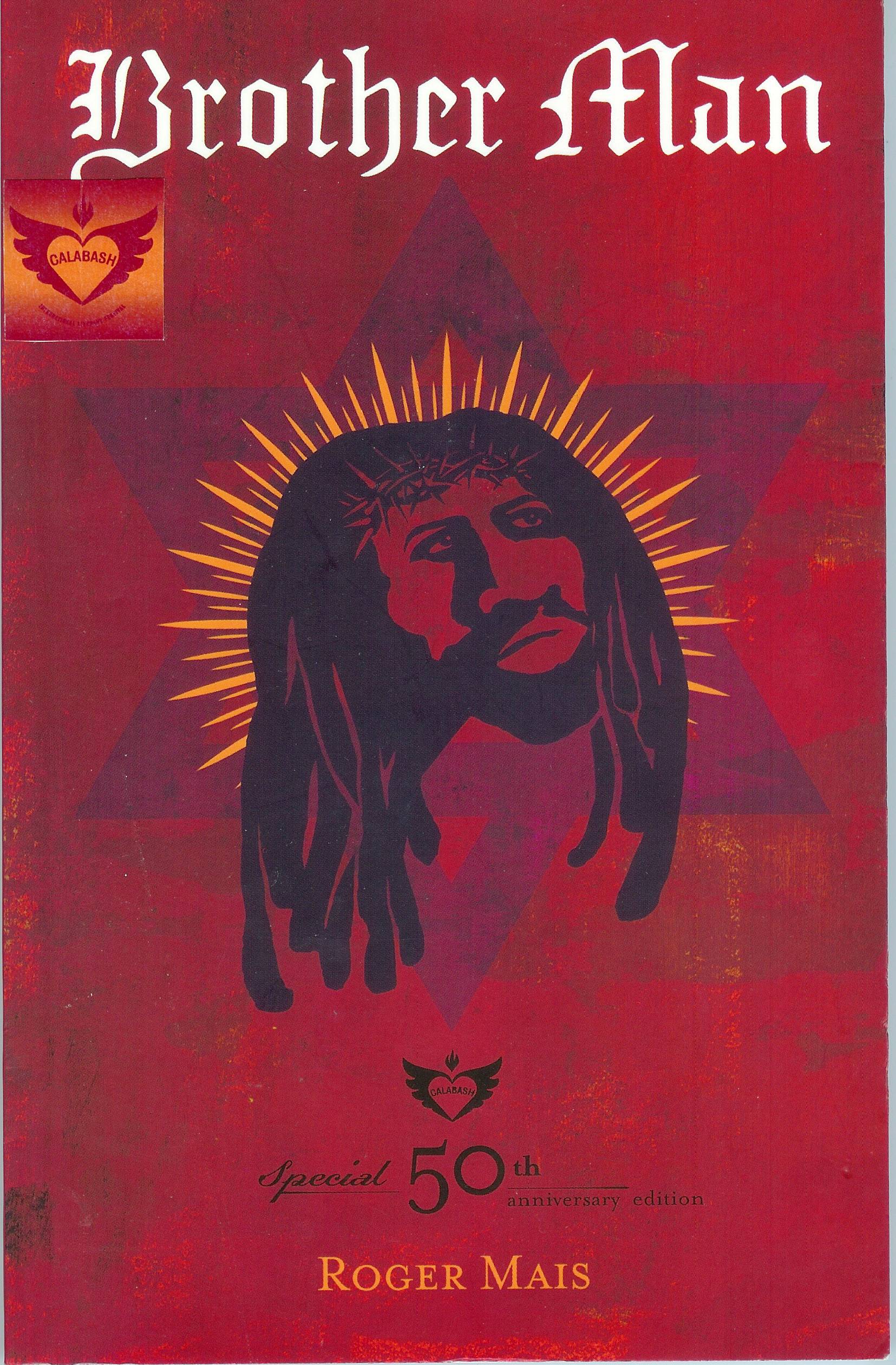

The novel wears a bold new cover, designed by artist Marcos Leme Lopes, who depicts a black Christ-like Rasta wearing a crown of thorns set against a lurid red backdrop.

“That’s something we want to do more of in the future, which is restore to publication classic books of Jamaica and the Caribbean,” said Channer. “Largely through the efforts of Kwame Dawes, we developed a relationship with Macmillan-Caribbean.”

The novel was received by the Calabash audience warmly, even though the reading of it stretched well beyond the average length of time for a literary reading or conference. Fifty years after the original publication, despite the romanticized characterization and the predictability of its New Testament typology, Mais’ prose still has the power to move, and the audience applauded at moments of tension in the text – at the conclusion of a sexually charged scene with Brother Man and his lover and, later, at a moment of his betrayal, when “Brother Man stood looking on like a man in a trance.”

Kwame Dawes’ energies as a writer have been set into motion from many sources, one of them unquestionably being Roger Mais. Not only was Dawes’ play One Love (2001) inspired by Brother Man, Mais’ example as a literary critic is complementary to Dawes’ own criticism, which is most comprehensively expressed in Natural Mysticism: Toward a New Reggae Aesthetic in Caribbean Literature. In it, Dawes describes how the language and concepts of reggae illustrate (and indeed interact with) the lives of Jamaicans socially, intellectually and linguistically; a ghetto song may illustrate the complexities of the artist in the community more candidly than a piece of literature from the same period. Thus it is with ease and coherence that in a single chapter Dawes can, for instance, penetrate the complexities of the music of Don Drummond, the poetry of Mervyn Morris and the fiction of Roger Mais. Until the advent of reggae, he explains, the writers with nationalism in their hearts and manuscripts used the literary forms of colonial tradition, which left little room for the voice of the working class and peasant majority population, many of whom don’t speak or think in the Queen’s English.

Mais, who died in 1955, prefigures Dawes’ critical stance. In an essay of pith and passion, Mais issues a call for a “hell-broth of revolt in Jamaican letters” to destabilize the prevailing and stodgy adherence to tradition. He says his peers are over-respectful of their literary masters. “If you would only wake up for long enough […] you would realize that these men in their day were the last syllable in modernity! Chaucer broke new ground and a lot of traditions, so did Milton, so did Shakespeare,” he writes, and the challenge becomes a rebuke. “You are disciples in the letter only, not the spirit. Chaucer would have laughed in his beard to watch you mimicking him, if he lived today” (183).

In the late 1960s, Barbadian man of letters Kamau Brathwaite took part in a critical debate about Caribbean aesthetics, out of which he produced the enduring essays about “Jazz and the West Indian novel” in which he argued that jazz invokes a way of seeing which perfectly befits the Caribbean community. Brathwaite called Brother Man an imperfect yet the most successful example of the jazz novels he had read. In it, “the violence is a kind of communal purgation. It involves the entire community of the novel, finally moving beyond the apparent chaos it brings, to that revelation of wholeness that one is aware of at the end of a successful jazz improvisation” (342).

It was with this spirit that Calabash invited Roger Mais and reintroduced Brother Man.

Dawes writes in the introduction to the anniversary edition, “[Mais] became a visionary who was in fact predicting the arrival of reggae, of Bob Marley, of Peter Tosh, of Don Drummond, of The Twelve Tribes of Israel, of Ites Green and Gold and of the current marketing of Jamaican society on Jamaica Tourist Board ads that sing in canned melodious notes the music of Bob Marley. But what Mais has preserved for us is the purer version of Rasta—Rasta as devotional force, Rasta as the voice of peace and love, Rasta as the force that makes Jamaicans see Africa with hope, Rasta as Christ-like, Rasta as something deeply rooted in the Jamaican capacity for survival” (9-10).

See www.macmillan-caribbean.com.

Works Cited

Brathwaite, Kamau. “Jazz and the West Indian Novel, I, II and III.” The Routledge Reader in Caribbean Literature. Edited by Allison Donnell and Sarah Lewis Welsh. New York: Routledge, 1996. 336-343.

Dawes, Kwame. Natural Mysticism: Toward a New Reggae Aesthetic in Caribbean Literature. Leeds, England: Peepal Tree, 1999.

Mais, Roger. “Where the Roots Lie.” The Routledge Reader in Caribbean Literature. Edited by Allison Donnell and Sarah Lewis Welsh. New York: Routledge, 1996. 182-184.