“We must create a second emancipation–an emancipation of our minds.”

“We must create a second emancipation–an emancipation of our minds.”

Marcus Garvey, 1929 anniversary of Emancipation in the English speaking Caribbean1

“Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery/ none but ourselves can free our minds.”

Bob Marley, “Redemption Songs,” 1980

Even most Jamaicans seem surprised to learn that Bob Marley’s line about “mental slavery” was adapted from Marcus Garvey’s call for a “second emancipation.” For the occasion of Marley’s 60th earthday, I’ve been meditating on what mental slavery and emancipation meant to Garvey, and to Marley, and means to the global audience that has made Marley a prophet of “One Love” (or a “real revolutionary”), and to the contemporary Jamaica embroiled in contentious debates about race and gender/sexuality.

I am convinced that the notion of a “second emancipation” from mental slavery is one of the great ideas in human history. When I look around for comparisons, I inevitably wind up with a scriptural frame of reference, such as Paul’s admonition: “ Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by the yoke of slavery.” (Galatians 5:1) Yet the specific linking of a second, mental emancipation to a prior, incomplete emancipation from physical slavery—this seems to have a uniquely Jamaican genealogy.

In a 1978 talk about Jamaica’s post-1948 “Cultural Revolution,” Victor Stafford Reid observed that after getting rid of the physical bondage of slavery, “the iron had not changed. It had merely entered our souls.”2 We find Marley calling for emancipation from mental slavery in 1980, just as Jamaica was abandoning its period of socialist revolution. And in the 1990s, Jamaican literary critic Carolyn Cooper observed: “The problem with emancipation is the fact that the chains on the mind are often even more binding than the chains on the body.”3

The suggestion that liberation from mental shackles is a process that must be re-imagined and re-enacted: that is an idea for the ages. Especially our own cynical, violent world. Our capacity to imagine meaningful resistance has shriveled, at the very moment when resistance is most needed. And so it is good to have Brother Bob’s voice still ringing in our ears, reminding us of the stakes beyond the struggles of our daily lives:

“I and I no come to fight flesh and blood

But spiritual wickedness in high and low places.”

In the high places:

“See them fighting for power

For they know not the hour.”

In the low places:

“Well what we know

Is just what they teach us

And we’re so ignorant

That every time they can reach us.”4

I’ve been writing about Bob Marley, the Rastas, and Jamaican music for many years now, in forums ranging from the Los Angeles Times to Cambridge University Press to European and American websites.5 But living in Garvey and Marley’s homeland exerts pressure on how I speak about the forms of emancipation that both men advocated, embodied, and inspired. I feel an urge towards self-censorship at the moment when private thoughts are translated into public words. When culture heroes are transformed into quasi-messiahs, it becomes near-impossible to translate their truths to our day, especially among those who are most invested in hero worship.

The pressure I feel on my mind and tongue tells me that the best way I can pay tribute to Bob at 60 is to speak from the heart. To acknowledge freely that I can only provide one personal perspective, which is that of an outsider, which carries its own strengths and limitations.

I would not be in Jamaica today if it were not for Bob Marley and Marcus Garvey. My first trip to Jamaica, for Sunsplash in 1987, coincided with Garvey’s 100th anniversary, and a lot of righteous dreads came down to the dance. I got ahold of a Garvey T-shirt. People expressed their delight that a foreigner would wear the iconic image of their national hero.6

I had already been involved with Jamaican music prior to 1987, as a songwriter and journalist. But that visit had a tremendous influence on me. All these years I’ve maintained a relationship, at some distance, with Jamaicans and their cultural expressions. As I developed a dialogue with an international audience through radio shows, writing, and public speaking, I was often forced to re-define my own presence in Rasta-inspired culture, or more broadly, Africana cultures. The world of “reggae music” was defined as a “black” domain, despite its primarily non-Africana audience. Within that domain, there was and is an unresolved tensions between “black liberation” and “multiracial redemption.” There were those who saw the two as deeply inter-related, neither possible without the other. And there were many others who believed that “black liberation” could only be enacted by opposition to all things “white” or European.

In my book On Racial Frontiers I wrote a section on Garvey as a forerunner to Marley and the Rastas. I found that, in contrast to other “racial equality” movements such as the Frederick Douglass wing of abolitionism, or the African National Congress in South Africa, both of which aspired to non-racial democracy, Garvey’s vision of a “Racial Empire” involved collaboration with the Ku Klux Klan. Garvey, like the Klan, wanted complete racial separation. Like the Klan, he hated mulattoes, as evidence of “amalgamation” or racial impurity. This was quite an irony, considering that it was the biracial Bob Marley who became the best-known international spokesman for Garvey’s “Africa for the Africans” philosophy.

In my book On Racial Frontiers I wrote a section on Garvey as a forerunner to Marley and the Rastas. I found that, in contrast to other “racial equality” movements such as the Frederick Douglass wing of abolitionism, or the African National Congress in South Africa, both of which aspired to non-racial democracy, Garvey’s vision of a “Racial Empire” involved collaboration with the Ku Klux Klan. Garvey, like the Klan, wanted complete racial separation. Like the Klan, he hated mulattoes, as evidence of “amalgamation” or racial impurity. This was quite an irony, considering that it was the biracial Bob Marley who became the best-known international spokesman for Garvey’s “Africa for the Africans” philosophy.

As I went on a book tour, I saw how easily a less than adulatory reference to Garvey could trigger hostile responses that shut down all possible discussion. This was manifest in Jamaica at the screening of the PBS documentary “Marcus Garvey: Reap the Whirlwind.”7 A friend here told me how Robert Hill, a Garvey scholar who had served as a consultant for the documentary, had broken down and cried the day after he was vilified at this screening.

Then there is the thorny issue of Bob’s Anglo father. Reactions I’ve encountered range from surprise (in the U.S.) at discovering this, to resentment that I would make an issue of a “black culture hero’s” mixed ancestry, to contempt or condescension towards Bob himself. As a youth Bob was often “styled a white man” and suffered tremendously because of this. Yet many youths today in Jamaica dismiss Marley by saying “he only made it because he’s half white.”

What Bob had to say on these matters ought to be a fundamental challenge to black vs. white racial binaries. We find Bob declaring that he was “neither on the black man’s side, nor the white man’s side, but on God’s side.” He insisted that Asians and Europeans could also be Rastas. He declared that “Unity is the world’s key, and racial harmony. Until the white man stops calling himself white and the black man stops calling himself black, we will not see it.”8 Marley defined himself primarily as a Rasta, not a black man, although he of course was a Pan-Africanist, and a proponent of black pride, within the larger definition of Rasta. Rasta was an African-centered, but at root a non-racial consciousness.

Then there is the question of the psychological influence of Marley’s absentee “white” father, given the way in which Marley imagined Selassie as both black and yet non-racial. In On Racial Frontiers I suggested that there was a link between Bob’s racial “ambiguity,” and his imagining Selassie as a “perfect father.” In an interview in Rebel Music, Jamaican scholar Garth White confirmed this point. White says explicitly that “Selassie became a father figure for Bob in a personal sense…Bob felt a personal affinity for Selassie based on rejection by his father.”

The way I interpret Marley’s music is influenced by the mixed company in which I hear it. Among the international network of reggae DJs which is part of my community, we read Junior Reid’s anthem “One Blood” as a straight-up declaration of non-racialism, straight out of Acts 17:26. But in Jamaica the song may take on different meanings. I watched Reid perform “One Blood” on February 6 near Emancipation Park. The song got one of the biggest responses of a tame event whose organizers relentlessly promoted the officially-sanctioned “One Love” theme. Reid is a Bobo, a Rasta sect whose members often express a belief in black supremacy. And in front of wall-to-wall Africana peoples in a “Little Africa,” “One Blood” could just as easily be heard as a variant of “Africa Unite.”

On February 5 I had my hair cut at the University of West Indies-Mona. We were listening to a Marley special on Irie-FM, and when “War” came on, my barber, a big-bellied man, came close to high-stepping with shears in hand. We sang along together, the words of Haile Selassie put to music by Bob Marley. The message is both about African Liberation, but also a declaration that justice cannot be achieved without a non-racial philosophy. The barber and I may have been moved by different parts of the same song, I reflected. While the lines about “without regard to race” are what most resonate with me, for my Afro-Jamaican barber, it may have been the lines: “We Africans will fight…and we know that we will win.”

The speaker of the words in “War,” Haile Selassie, was a devout Christian (Ethiopian Orthodox). His faith surely shaped his view that non-racialism (skin color is no more important than eye color) was the best way to get rid of perpetual violence. So if we follow Garvey’s advice to look to the roots, where might this lead us?

Think again of the Biblical parallels. A once strictly Jewish faith becoming “a house of prayer for all people.” This evolved into a new recognition of our common humanity through a common Creator—“Out of one blood God created all nations that dwell on the face of the earth.” This is one of the most important scriptures in Rasta culture, as well as in the history of abolitionism. So then how does a “racial empire” fit in with the necessity to eradicate racialism?

Garvey argued that in a “racial empire,” black people should reject the heroes, and thought patterns, of other races. “Any race that accepts the thoughts of another race…becomes the slave of that other race,” Garvey argued. And he insisted: “To emancipate yourselves from that you must accept something original, something racially your own.”9

Garvey believed that Africana peoples must be emancipated through a “racial hierarchy,” a religious notion of race pride utilizing a “racial catechism,” which would be used to instill and enforce racial allegiance. His black Zionism played an enormously important role in instilling self-respect among diasporic peoples. But it was also much like a theocracy. Politically, the “ideal state” posited by Garvey combined fascism (as Garvey himself explicitly said), and imperialism. “African Fundamentalism points to Imperialism,” he insisted.10

Now, “every man has the right to decide his own destiny.” Every individual and every cultural or ethnic group has the right to name themselves and define their objective as they see fit. I have no argument with any self-definition of Africana peoples, or any other group. I agree that we still have a lot of work to do before the majority of human beings can acknowledge African peoples as a cornerstone of world civilizations. Furthermore, aside from Garvey’s use of racial language, the critique of accepting thoughts that are not our own could be very well applied to Jamaica’s neo-colonial dependency on North American commercial culture.

But I am a member of the outernational community that has been inspired by Jamaican culture heroes such as Garvey and Marley. As a man with allegiances to several cultural worlds—as an Oklahoma-born, Irish-American, Spanish-speaking father of biracial children whose skin color is about that of Bob Marley—I have had to ask myself: where do I fit in? Or do I try to fit in? I rejected the fundamentalism of my Christian parents, so why would I accept it just because the speaker has a different skin color? Or can carry a tune and a rhythm better than the people in the church where I was raised?

Tolerance and pluralism are core values for me. So when I read Garvey declaring that “whites” were the “natural foe” of Africana peoples, “irrespective whether they were American, English, French, or Germans,” then I must recognize a racial mythology that conflicts with my core values. And as a part of the audience, and as a promoter of a culture that sometimes expresses intolerant perspectives on race or gender, then I have the obligation, as Sister Carol once said to me, to express my dissent. This is part of what emancipation means.

I do not presume to tell Jamaicans anything about Marcus and Marley, as Jamaicans. But the ideals they have inspired are an international phenomenon. They have been taken up and sung by so many millions of people, and interpreted in so many ways, that the ideas and emotions associated with Marley’s songs of freedom cannot be owned. The words come from a Jamaican, but the audience is international. There is a relationship between the speaker or singer, and the audience. “The speaker is under tutelage of the audience,” as Molefi Asante once said.11

So from this perspective, I pose the question implied by my title: has Marcus Garvey’s definition of a “second emancipation” as a “racial empire” been transfigured by Marley and the Rastas? (Transfiguration has religious roots, but more broadly, transfiguration can refer to any sudden transformation in outward appearance which also indicates inner change.)

Old Testament prophets began to evolve beyond the idea of a merely tribal Jewish God. The Rastas, a “community of prophets,” underwent a similar evolution, as they interacted with a global audience. They had sighted the Creator “through the spectacles of Ethiopia,” as Garvey said. But like the Jews in Babylon, they came to understand that this was an international God. Thus when Marley voiced, on a global stage, the metaphor of an Exodus of Jah people, he conveyed a sense of community that in the final analysis was not racial. When Marley sings “none but ourselves can free our minds,” he echoes Garvey. But the “we” here has changed. Marley’s interviews make it clear that he saw this process of emancipation as multi-racial, although people of African descent claimed a privileged role as the “cornerstone” of this collective emancipation.

If we were to ask the question, emancipation from what, and towards what, the answer could not be definite. Certainly one can point to the transformations, in Rasta culture, of racialized slogans to less racial forms. Early Rastas said “death to white oppressors.” This later become “death to black and white oppressors,” and later still, “death to black, brown, and white oppressors.” The opening of a concept of oppression that goes beyond race leads towards much broader forms of emancipatory thinking, such as Marley’s line in “Survival” that we live in “a world that forces lifelong insecurity.”

If we were to ask the question, emancipation from what, and towards what, the answer could not be definite. Certainly one can point to the transformations, in Rasta culture, of racialized slogans to less racial forms. Early Rastas said “death to white oppressors.” This later become “death to black and white oppressors,” and later still, “death to black, brown, and white oppressors.” The opening of a concept of oppression that goes beyond race leads towards much broader forms of emancipatory thinking, such as Marley’s line in “Survival” that we live in “a world that forces lifelong insecurity.”

Emancipation from mental slavery thus requires resistance against a multi-faceted Babylon System, of which racialism is just one part. The nature of my own attraction to Rasta has to do with I-and-I consciousness. This ideally leads not only to non-racialism, but to respect for all life. If the creator is everywhere, then we must show respect for all Creation. This requires some sense of kinship with people who look different from us, or hail the Creator by a different name, as well as with Mother Nature. Hence, two cores ideas of Rasta, as popularized by Marley, are trodding lightly on the earth, and non-racialism, i.e. One Blood.

But in the real world, Rasta is all but dead on the streets of Kingston today. When I listen to Irie-FM in a cab on Hope Road passing Marley’s old house-turned-museum, it seems almost entirely disconnected from the new Kingston, the new T.G.I.F. full of SUV’s in the parking lot.

Sometimes I look around here, and think that it’s really the concept of a “racial empire” that has triumphed, along with American-style consumerism. Many of my students express a reflexive belief in “Black dominance.” They refer repeatedly to the “white man” as the symbol of all they think they oppose.

Binary thinking, black/white or otherwise, is a form of mental slavery. But it is difficult to even talk about the possibility of commonality and difference co-existing. Efforts to establish a common language are read as an attempt to whitewash the cultural differences we treasure.

The problem is “the insidious confusion of race with culture which haunts our society,” as Ralph Ellison once wrote.12 We get our appearance (our phenotype) through our genes, but our culture is a learned language. So to think that we can determine someone’s intelligence or culture by their skin color or phenotype is one of the most fundamental forms of mental slavery. It is a “diseased imagination,” Frederick Douglass once said. It is also a “master metaphor,” as Kenneth Burke puts it, and as such, a mental shackle that prevents us from developing the broader sense of family or kinship that is a precondition for dealing with all our contemporary crises.

If we can project all blame onto our “other” or enemy, then we don’t have to recognize the ways in which we are similar to our other. A colleague tells me about a student who announced that North Americans were the Antichrist. She herself was wearing a T-shirt with an American flag. Presumably, like virtually all my students, she was looking at the world through North American cable TV, and imbibing a fundamentalist message that divided the world starkly between good and evil, just like the leaders of the nation she claimed to oppose.

The Jamaica now celebrating Bob Marley’s 60 th earthday has barely begun to come to terms with its neo-colonial relation to American commercial culture. In a column in the Daily Observer, Becki Patterson observed that hedonist partying and “the worship of material things” have become “an essential part” the new Jamaican way of being, just as it is for Americans of all colors.13 But many people imagine that their “blackness” provides them some sort of moral immunity for copying the worst of American materialism.

African unity in the service of movement out of Babylon seems to me like an emancipatory idea. African unity as a version of racial self-absorption seems to be another form of mental slavery, “just another illusion.” I can only speak for myself here. But at this hour, I am much more concerned with how people live than their skin color, language, faith, or sexuality. Surely emancipation in the 21 st century requires us to begin asking questions such as: What systems of domination do our lifestyles support?

It seems we need “a new framework for emancipation,” as Horace Campbell wrote.14 One overdue manifestation of that might be an emancipation from a fixation on Bob. Will we be forever milking Bob? I have been impressed by how Subcomandante Marcos of the Zapatistas has framed the issue. As he travels around Mexico, he says repeatedly that the Zapatistas, while revolutionaries of a sort, think of themselves and expect to be treated as just one point of reference, rather than as models. Investing too much in one model is a form of mental slavery that prevents the multi-centeredness and flexibility people need to deal effectively with their own unique challenges. As Bob sang, “I know it’s impossible to go living through the past. Things are not the way they used to be.”

Jamaicans are currently involved in a process of “monumental heroization,” as Petrina Dacres has written in Small Axe.15 During the racialized controversy over the unveiling of the “Redemption Song” statues in Emancipation Park, Carolyn Cooper spoke of “the grandeur of emancipation.” “Our emancipation monument needs to be unequivocally majestic,” she wrote.16

The legacy of slavery, abolitionism, and emancipation is certainly “monumental.” But the memory of slavery in Jamaica, in its monumental form and in popular consciousness, seems to involve African peoples breaking their own chains, and then showing implacable opposition to their former white masters. Yet both slavery and the opposition to slavery were international and “multiracial” phenomena. I am struck by the degree to which the whole history, literature, and culture of abolitionism has all but been erased from public memory in this part of the Caribbean.

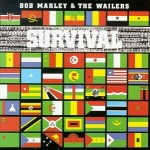

The ecstatic reception of Marley in Europe (as well as in Asia and Africa) was foreshadowed by the enthusiastic response to Frederick Douglass and the abolitionists in the 19 th century. The deep roots of the international mobilization against slavery, and the movement towards new forms of emancipation, can be seen in the drawing of a slave ship which was reproduced on Marley’s masterpiece Survival.17 This representation of the middle passage was produced by English abolitionists beginning in the 1780s as a tool to achieve the first emancipation.

The international and multiracial coalitions that successfully mobilized against slavery, and various forms of apartheid, are also heroic movements that need to be memorialized. The legacy of that resistance–an immortal monument of our struggle towards a second emancipation—is everywhere visible and audible in the world’s embrace of Marley’s music. Perhaps that is the most majestic memorial to “the grandeur of emancipation.”

NOTES

1) Philip Potter, “The Religious Thought of Marcus Garvey,” in Rupert Lewis and Patrick Bryan, Garvey: His Work and Impact (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1991), 162.

2) Victor Stafford Reid, “The Cultural Revolution in Jamaica after 1948,” talk delivered at the Institute of Jamaica in 1978; reprinted in The Routledge Reader in Caribbean Literature, ed. Alison Donnell and Sarah Lawson Welsh (1996), 177.

3) Carolyn Cooper, “Righteous Reggae,” Jamaica Observer 12-14, August 1994, quoted in Norman Stolzoff, Wake The Town and Tell The People: Dancehall Culture In Jamaica (Durham: Duke UP, 2000), 244.

4) Later in “Ambush In the Night” Marley inverts this verse, in a powerful expression of the self-determination that can come from having alternative sources of knowledge:

“Well what we know/Is not what they tell us

‘Cause we’re not ignorant, I mean it/And they just cannot judge us”

5) My music writing and some radio shows can be accessed at http://www.gregorystephens.com

6) My first impressions were published as “Fashion Dread Rasta: On the One in Jamaica with Bob Marley’s Children,” Whole Earth Review (1987).

7) Reception of Whirlwind : Marcus Garvey’s son Julius Garvey got into a shouting match with the American producer Stanley Nelson after a showing in Jamaica, calling the film “a lynching of the character of Marcus Garvey.” Basil Walters, “Uproar over Garvey Film,” Jamaica Observer (Feb. 22, 2001).

8) Ian McCann, Bob Marley: In His Own Words (London and New York: Omnibus Press/Book Sales, 1993), 54. I have taped interviews with Marley in my possession in which he affirms that a white man can be a Rasta, that Rasta is non-racial, that Asians can also sight Rasta, etc.

9) Marcus Garvey, “African Fundamentalism,” in Robert Hill and Barbara Bair, eds., Marcus Garvey: Life and Lessons (University of California Press, 1987), 7-8, my emphasis.

10) racial catechism, and Imperialism: Life and Lessons, xxv; 23. Fascism: “We were the first Fascists,” Garvey told Joel A. Rogers. Garvey wrote that “Mussolini and Hitler copied the programme of the UNIA.” Black Man 2:8 (December 1937), 12; Life and Lessons , lviii.

11) Molefi Asante, The Afrocentric Idea (Temple UP, 1987).

12) Ralph Ellison, Collected Essays (Modern Library, 1995), 43.

13) “Party is the post-modern replacement for religion and the worship of material things is an essential part of this way of being.” Becki Patterson, “Party, Opiate of the people.” The Daily Observer 1-12-05.

14) New framework, Horace Campbell, “Garveyism, Pan-Africanism and African Liberation in the Twentieth Century,” in Rupert Lewis and Patrick Bryan, Garvey: Work and Impact (Africa World Press, 1991), 170.

15) “monumental heroization,” Petrina Dacres, “Monument and Meaning,” Small Axe 16 (September 2004), 149.

16) “the grandeur of emancipation,” Carolyn Cooper, “Enslaved in Stereotype: Race and Representation in Post-Independence Jamaica,” Small Axe 16 (September 2004), 160. “I observed [on the TV show Question Time (CVM)] that the racial politics of the monument could very well be conceived as ‘out of one white woman, two stark-naked black people.”

17) The history behind the image on the slave ship reproduced on Survival is discussed in Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780-1865 (Routledge, 2000), 16-40.