“Colección Romántica”

“Colección Romántica”

Juan Luis Guerra [Karen 2000]

[NOTE: Parts of the following essay come from a chapter originally commissioned (but then cut) by Rebecca Walker for a book she edited, What Makes a Man: 22 Writers Imagine the Future (Riverhead Books, 2005).]

INTRODUCTORY SKETCH OF THE ALBUM AND ARTIST

Colleción Romántica is a sort of “greatest hits” of Juan Luis Guerra’s love songs. Of the 20 songs, 14 have been re-mastered, of which six were re-mixed. There is a live version of “Estrellitas y Duendes,” recorded in Madrid, which sends a thrill through me when I hear the enraptured Spanish fans singing along. And there are five new recordings of songs originally done in the style of salsa (“Quisiera,” “Razones,”), and merengue (“Tú,” “Ay Mujer,” and “Amor de Conuco”), now mainstreamed in a pop or rock style. These are not high points for me, but if they introduce Guerra to new audiences, they have served their purpose (think Marley’s Legend). The remixes are an improvement, revealing with greater clarity Guerra’s compositional skills.

Guerra is the son of a professional baseball player in the Dominican Republic. He studied at the Berklee College of Music in Boston on scholarship, and the jazz idiom has had an obvious influence on his arrangements. Merengue has been his bread and butter. Guerra in fact is as important to the genre of merengue as Bob Marley was to reggae. They both re-defined the genre, became the genre, and transcended the genre, because their vision could not be contained in any one form.

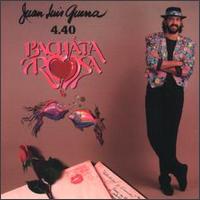

Guerra achieved fame in part through re-inventing a traditional Dominican style, the formerly disreputable bachata. He has also had a long love affair with Afro-pop, especially soukous, with often spectacular results on his songwriting. Although he is best known for his love songs, Guerra has also written provocative political songs like “Si Saliera Petroleo,” or other tunes that treat social concerns of his homeland, such as the classic “Ójala que Llueva Café” or “Visa Para un Sueño.” My favorite Guerra album is Areíto (1992), which has more politically-oriented songs, and where his fusion with African music reaches a high point, such as on the collaboration with Diblo Dibala, “La Costa de la Vida.” Most Guerra fans would choose the Grammy-winning Bachata Rosa (1990) as his best album.

Guerra achieved fame in part through re-inventing a traditional Dominican style, the formerly disreputable bachata. He has also had a long love affair with Afro-pop, especially soukous, with often spectacular results on his songwriting. Although he is best known for his love songs, Guerra has also written provocative political songs like “Si Saliera Petroleo,” or other tunes that treat social concerns of his homeland, such as the classic “Ójala que Llueva Café” or “Visa Para un Sueño.” My favorite Guerra album is Areíto (1992), which has more politically-oriented songs, and where his fusion with African music reaches a high point, such as on the collaboration with Diblo Dibala, “La Costa de la Vida.” Most Guerra fans would choose the Grammy-winning Bachata Rosa (1990) as his best album.

During the mid-1990s, Guerra reportedly focused on running his evangelical church and TV/radio. He returned in 1998 with No Es Lo Mismo No Es Igual, which is by turns introspective and roof-raising. The gospel-style rave “Tengo Un Primo” is alone worth the price of admission.

During the mid-1990s, Guerra reportedly focused on running his evangelical church and TV/radio. He returned in 1998 with No Es Lo Mismo No Es Igual, which is by turns introspective and roof-raising. The gospel-style rave “Tengo Un Primo” is alone worth the price of admission.

AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT

What follows is a meditation on some recurring motifs in Juan Luis’ Colleccon Romántica. It is based on material edited out of a book chapter, “A Sojourn Through Celibacy: Learning a Second Language of Love.” This chapter is a re-consideration of the meaning of manhood, a look in the rear-view-mirror, with Guerra’s music in my ears, during an eight-year period in which I was celibate, and became fluent in a second language, primarily through speaking Spanish with my children.

It was while in sexual exile for eight years that Juan Luis Guerra’s romantic poetry rained on my imagination. My translations of this ironic encounter follow. If you don’t speak Spanish, this may serve as one entry point to Guerra’s artistic vision. For those who know the language and music better than I, pues, aquí se ve la evidencia de lo que pasa cuando un Gringo anda con el semen inutilizado atorandole el cerebro.

LEARNING A NEW LANGUAGE OF LOVE

“Canta corazón

con un ancla imprescindible de ilusión

Suea corazón

No te nubles de amargura“

My free translation of this verse from Juan Luis Guerra’s “Burbujas de Amor” would be as follows: The language of love is a necessary illusion, which anchors the heart to a greater reality, where clouds of bitterness will not blind it. But if I were to translate this literally, it wouldn’t sound quite right:

“Sing heart, anchor yourself to the indispensable illusion

Dream heart, don’t cloud over with bitterness.”

I’ve been listening to Juan Luis Guerra’s music for over a decade now. Many times, his music has moved me deeply, lighting a fuse to emotions, to reservoirs of hope, that I barely knew existed, which I do not seem to be able to access through English. The package seems to be something more than the sum of the parts. Guerra’s romantic sentiments are expressed in such lovely poetry, sung with such conviction, and backed by such gorgeous (not to mention often fiery) musical arrangements, that they light a fire in my soul. I feel cleansed, sometimes, after listening to his love songs. He often sings directly to the heart, as if the heart were a sentient being, and resided within a semi-autonomous place. And clearly, as poets of all languages have told us, the heart has reasons which reason knows nothing of.

Yet it remains a bit of a mystery as to why my own heart is open to this poetry in other languages, especially in Spanish, a Romance language with Arabic as its cornerstone. My heart remains fiercely unmoved by, even opposed to, romantic sentiments expressed in English. It is not entirely a mystery, however, that we often learn about new dimensions of being through interacting with an “other,” whether this be a beloved, or a new culture, or a great work of art (or indeed, an enemy). For instance, I am often inspired by praise songs sung by Rastafarian reggae artists. When I put their lyrics on paper, I see that the language is often identical to the praise songs I heard as a youth in a fundamentalist church. And Christian praise songs, at least as sung by WASP Protestants, leave me cold. They raise all sorts of defenses. Yet the Rastas sang my roots back to me in a new style, with a new conviction, addressed to a god sighted through a face of a different color. This tradition comes alive for me, through these inflections. Rastas taught me the importance of faith, taught me to be more tolerant of faiths I do not share, for I see more clearly through them that faith can move mountains.

A similar dynamic is at play when an artist such as Juan Luis Guerra re-invents the language of love for someone like me, invests romantic love with emotional and indeed spiritual possibilities of which I had been previously unaware. Or if I was aware, the tradition that fuses romance and worship in English (adoration) usually did not come alive in my consciousness. I would make some exceptions here, such as Irish lyric poetry, and the sort of language of romance that D.H. Lawrence articulated, in which inter-gender conflict, including a certain resistance to the romantic other, retains an honored place, as a mystery in its own right.

Part of what keeps me on board with Guerra is that there is often a darker undertow to his romantic lyricism. There is a subtext of conflict, almost as if he were driven to heights of lyric invention by exasperation, or desperation, in the face of a beloved who is clearly not always seduced or impressed by his declarations of undying love. Only occasionally does the conflict break into the open and become the primary subject matter of one of his songs. Such is the case with “Seales de Humo,” a song about the difficulties, sometimes even the impossibility of communication between lovers (incommensurability, as academics say). This has long been one of my favorite Guerra compositions, in part because it speaks so eloquently to my own desperate attempts at communication with a woman:

“Te mando seales de humo

como un fiel apache

pero no comprendes el truco

y se pierde en el aire…

Que voy a hacer

Inventar alfabeto en las nubes?”“Like an Apache I send you smoke signals

but you don’t understand

and my efforts disappear into thin air.

What am I supposed to do,

Invent a new language with clouds?”

This speaks to a sense I have often had of speaking across great distances or emotional chasms, and of going to great creative lengths in an effort to bridge that divide, only to meet utter incomprehension, indifference, or hostility.

A second reason why “Seales de Humo” is one of my favorite Guerra songs is that midway through it shifts musical and lyrical gears. As what was a ballad modulates and kicks into a serious groove, the lyrics also modulate, as so often with Guerra, into a metaphoric language meant to dissolve the separation or distance between the lovers. The female chorus of the group 440 repeats the refrain:

“y tu amor me cubre la piel

es como alimento

Que me llena el alma de miel

Sin tu amor yo muero”“Your love covers me like a second skin

It nourishes me and fills my soul with honey

Without your love I would perish.”

And here I find, even as I sing along with Guerra, that I reach the limits of my empathy. Although I am willing to go to great lengths, to invent new languages, in order to reach out to someone who is important to me, even if the face of repeated evidence that the message is not getting through, I cannot feel sympathetic to the notion that I would die without someone’s love. Yet this neediness is absolutely central to Guerra’s vision. He declares his inability to live without his beloved over and over again, albeit with lyrical virtuosity.

“Nada es igual

todo es frio si no estas…

todo es vano si no estas”

(“Palomita Blanca”)“Everything is cold and without meaning

if you are not with me”

“Y si no estas conmigo

Todo va muriendo

Y no puedo soar”

(“Ay Mujer”)“Everything seems to die, and I cannot dream

if you are not with me.”

Even given the omnipresence of this sentiment in popular love songs, Guerra’s neediness goes to extremes that strike me as both beautiful and frightening. He not only needs to be with his lover at all times, he needs to perform acts of magic, of transfiguration, so that the distance between their bodies, and hence their beings, is demolished.

“Viviré cada segundo pegadito a ella

como medallita al cuello”

(“Vivire”)“I will live each second fastened to her

like a medallion on her neck.”

“Quisiera ser el aire que respiras

quisiera ser el rizo de tu pelo

quisiera ser tu septimo sentido

… el calcio que te dan tus vitaminas”

(“Quisiera”)“I would like to be the air that you breathe, the curl of your hair,

your seventh sense, the very vitamins that nourish you.”

The desire, or demand, to demolish all distance and become one with the very essence of the beloved is perhaps the dominant sentiment of Guerra’s romantic poetry. He wants to be inside her, stuck to her, all around her. Not only does he want to be the calcium of her bones, he wants to be the very air she breathes. Like a force of nature, he wants to burn himself into her cheeks “como el sol en la tarde” (like the afternoon sun), and having attained this, or perhaps having recognized the impossibility of attaining this, he will become

“un planeta de celos

esculpiendo una canción”

(“Estrellitas y Duendes”)“a jealous planet/carving out a song”

There remains apart of me, even while emotionally immersed in Guerra’s world, that observes: this is what psychologists call co-dependency. Complete withdrawal from sexuality and romance and complete immersion in that realm may both be a “source of valuable ecstatic abilities,” as Max Weber once wrote. Yet if I were forced to decide which state of being carried greater dangers, complete immersion in or withdrawal from romantic love, part of me is more suspicious of immersion. I see romantic obsession as unhealthy, if not balanced by periodic withdrawal. Ultimately, obsessive love or hate both strike me as equally blinding. I can affirm my preference for the blindness produced by love. Yet my sojourn through celibacy, initiated by my efforts to process the hatred toward me by the mother of my children, have left me hungry for a third way, in which love and hate are parts of a spectrum, in which immersion and withdrawal each have their valued place.

Confronting the desire for abandon to a beloved, and for complete union, as expressed by Guerra, I find myself wondering: Who is the market for such sentiments? From whence comes the longing for enraptured romance? And why do I feel such resistance to the notion of total surrender? It would be hard to deny the evidence that women have historically been, and continue to be, the prime target of and consumers of the romantic language of surrender and abandon as a path to rapture.

This sort of ecstatic language of romance seems “soft” to my traditionally “masculine” self. I am unwilling to see it as a defect, or a masculine myopia, that I want the language of love anchored in something beyond my skin, or the skin of a lover; oriented to something outside of man and woman and their mutual neediness. I want love to be grounded in an awareness of suffering and conflict beyond that caused by our beloved withdrawing, or refusing to fill our every need.

Every year when my partner DJ RJ and I do a show of the “Best Conscious Reggae” tunes, we have to scramble to include female artists who meet our definition of “boom shots”: both lyrically conscious and musically compelling. There are very few conscious female artists in this field. The focus of female artists in Caribbean music is almost entirely on their relationships with men. Male artists in this genre, by contrast, give voice to a wide range of concerns, including romance, but routinely extending to political critiques, prophetic visions, environmental issues, etc. The absence of female artists creatively expressing similar concerns leads me, in frustration, to ask: Why are women artists so wrapped up in concerns about men? Didn’t men originally write those songs, and that script, in most cases? In reggae, as in most forms of popular music, male writers and producers usually scripted a narrow sexual role for women. But this dynamic seems to have taken on a life of its own. As more female artists began writing their own tunes, they continue to center their concerns, for the most part, on their relationships to men. And in the final analysis, I find this boring.

I have had to admit that I have a blind spot in the language of love. My enthusiasm for Latin American music is to some degree independent of its lyrical content, but it is also an effort to correct this blind spot. Approaching romance in Spanish allows me to feel emotions I would reject in English. I tune out a sub-genre within reggae, “lover’s rock,” which is dedicated to romance, and I rarely pay attention to love songs in rock or pop or any other style sung in English. But I feel genuine admiration for someone like Juan Luis Guerra who speaks a language of transcendent love, which seems to be what many women want to hear.

Guerra is a songwriter who uses a literary style of poetic expression. His song “Frio Frio” adopts an image by the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca, of love being both hot and cold, like the water of a river or the water of a fountain. It contains the following lovely verse:

“Tu amor lo guardo dentro de mis ojos

como una lagrimita

y sin lloro para que no salgan

tus besos de mi vista”

He holds his beloved’s affection in his eyes like a tear, without ever letting that teardrop fall, so that her kisses never leave his vision. This is a poetic vision of what we mean when we say someone’s eyes were “brimming with emotion.”

Guerra often constructs his language of love with metaphors taken from bodies of water. For instance, in the beautiful ballad “Burbujas de Amor,” he imagines becoming a fish so that he can be surrounded by an environment in which his beloved lives (a fishbowl). His vision of rapture is to“vivir siempre mojado en tí” (live always soaked in your love).

I find it easier to identify with romantic love when it is combined with a heightened sensitivity to nature. In “Amapola” Guerra anchors the song with this lovely image, in order to make explicit the similarity between the raptures that romance and nature can inspire:

“un arcoiris me pintó la piel

para amanecer contigo.”(a rainbow painted my skin

as I greeted the dawn with you)

In this same song, Guerra invites his lover to ride horseback along a river at night.

“si te da frio te arropas

con la piel de las estrellas”(if you get cold you can wrap yourself

with the skin of the stars)

The warmth provided by a blanket of stars should evoke some residual heat among anyone who remembers making love under the heavens at night.

I also find it easy to identity when the awakening of romance is worded in such a way that it can also evoke an awakening of consciousness. Thus in “Frío Frío” Guerra sings: “pudiera ser un farolito y encender tu luz” (I could be a lighthouse and fire up your light”).

Sometimes I feel as if Juan Luis Guerra were singing from the Everest of romantic love, whose peaks I know I will never scale. He enables me to imagine this, to feel this passion, by using metaphors that speak to my own deepest passions. But I would never aspire to be an appendage of a woman, as Guerra sings in so many ways. I would never want to be her “shadow,” an image he uses in “Amigos.” I could not sing Glory to a woman, unless it be the mother of creation.

It’s not as if I only feel that way about surrender to a woman. I feel antipathetic about the notion of total surrender to any human. But the urge to sing Glory continues. During my sojourn through celibacy, however, this urge has been redirected.

Being all too human, I know that clouds of bitterness sometimes still do darken my heart. I know with unmistakable certitude that in this moment my heart rebels against the idea of pleasuring a woman. I can’t fully explain this, and I know that this resistance could melt away in a moment. But this resistance has much deeper roots, comes out of a long history of rebellious determination to follow my own muse, to withdraw from all the fashions, the beliefs, the ideologies, the lifestyles which run counter to the counsel of my heart.

I do not feel that sexual pleasure can heal my own wounds. Or perhaps I do not want to be fully healed, since the rawness of some repressed emotions in my heart is a source of creative energy. The longer I have lived outside the embrace of a woman’s arms, the less willing I have been to imagine a return under any circumstance in which the motivation is merely the getting or giving of physical pleasure.

The specifics of my story, in which hatred projected onto me has made me resistant to the idea of pleasuring a woman, have forced me to think about forgiveness in new ways. How is one to process what one feels is undeserved hate or persecution? Again I find new meanings in Guerra’s lyrics, read through my own sojourn:

“dile… que no he olvidado y que he sufrido

Ya lo sé, Cuento mi error

Pero entiendo que el amor todo le perdona”

(“Palomita Blanca”)“Tell her that I have not forgotten and that I have suffered.

I already know, I am aware of my errors,

But I understand that love pardons all.”

What sort of love would forgive unremitting hate? Linking my own story with the public process of coalition-building, I’ve learned some lessons. Attempting to communicate with someone who has traditionally seen “us” as their enemy requires two important changes in perspective. It requires that we learn to agree to disagree on some issues, rather than seeking to punish, or convert, those who disagree with us. And having tabled some sources of conflict, we must learn to focus on some shared interests, even as distrust or dislike continues. In my own life, I find it easy to agree to disagree on almost any issue with people who are willing to focus with an open mind on one shared interest: what is in the best interest of our children? (And I mean this in terms of future generations, as well as literal children that we have co-created).

After eight years of my sojourn through celibacy, I can reaffirm Guerra’s belief that love is a necessary illusion to anchor one to a reality apart from bitterness. My imprescindible ilusión” is of other kinds of love…love of my children, love of justice, love of the earth, all guided by a love of future generations.

As old folks say, I feel I have been “called and set aside.” And in this separate reality, a parallel existence fuera del alcanze de la mujer, I bide my time. I sometimes long for, and I am certain I retain the capacity, to give and receive pleasure. But I only feel willing to abandon myself to pleasure if it is a byproduct of something greater than man and woman.

* * *

I would like to dedicate this essay to my friend Sandra Pedregal, formerly my Spanish teacher in San Diego, and to Sela, mi hija, mi mejor estudiante, mi maestra verdadera.

1 comment

Paul H. says:

May 5, 2019

Listening to Areito for the zillionth time as I came across this article. Still blown away by how great this album holds up, even after 15+ years. Bachata Rosa is a great latin pop album, but Areito is a serious piece of work. The arrangements are dazzling, the lyrics are sharp and sometimes heart-wrenching, and the production-value is superb. Credit to Guerra as producer and writer. An artist in the truest sense of the word.