Suzzana Owiyo: Mama Africa, ARC Music, 2004

Suzzana Owiyo: Mama Africa, ARC Music, 2004

The musical genre is “Luo pop” from Kenya. You can look it up, but I’ll tell you what it—or rather this example of it—sounds like to me. To my ears it sounds like some of the best musical bits plucked from here and there across Africa (and a few other places) and then lovingly amalgamated into something truly potent. It’s not unique music as much as uniquely blended music, for a sparkling, beautiful and surprisingly consistent whole. Probably wholesome too.

The evidence is on the very first track, “Kisumu 100”, an optimistic tune with strong musical hooks. This starts with a brief reminder of luscious, King Sunny Ade-styled Nigerian juju, followed seconds later by a male vocal phrase that seems to have come from the continent’s Arabic north. The arrangements include a west African soukous kind of zippiness and instrumentation, and across the whole rides Owiyo’s determined voice, strong and urgent with, I swear, a vocal style straight from South Africa. The second track is another catchy piece, with that South African slant again, but the main accompaniment this time is acoustic guitar. On “Ngoma”, a powerful lead vocal weaves its way over a complex rhythm that sounds like several dozen hand drums being tapped, slapped and whacked in unison and otherwise; they could almost be Brazil’s Olodum.

The title track slows things down with a subdued arrangement for a very pretty ballad, Owiyo singing sensitively (yet still powerfully) over a strummed guitar. The memorable tune, swaying rhythm and pure, straightforward vocal of “Vyie” make it another highlight. Then there’s “Suna Ka Ngeya”, whose pounding, funky beat is perfect for the quick call and response vocals between lead and backup singers. The most heart-rendingly beautiful piece, though, is Owiyo’s tribute to her grandmother called “Masela”, with a lively rhythm and simple, touching lyric, sung in English: “Where are you, my dana Masela? I miss you. I love you.” The supportive musicianship here, and everywhere else onMama Africa, is simply outstanding.

Suzzana Owiyo has been compared to Tracy Chapman. I can hear why—their voices, and sometimes their phrasing, are similar. But Owiyo is no Chapman clone; she is a truly gifted singer and a self-contained, fully contributing, unique artist. She has absorbed a delightful array of influences, and composes with a dazzling, creative imagination. Mama Africa is a delight from start to finish.

Ska Cubano: Ska Cubano, Casinosounds, 2004

Ska Cubano: Ska Cubano, Casinosounds, 2004

I dunno. These guys seem to think that music is about passion, and fun, and dancing—stuff like that. Here they are, banging away on piano, bashing their drums, singing, blowing horns and enjoying themselves. I’m not saying it’s chaotic by any means, and yes, there are even a few relatively subdued moments, but that attitude!—you can hear it; it’s always in there. Throughout the album, imagine. You’d almost think life was worth living after all.

Even the sleeve notes by Peter A. Scott get into the act with an irrepressible, fun approach; sure, they’re intelligently written and highly informative, but what happened to respect? Well, okay, they do actually show a heckuvalotta respect for the band’s dismayingly deep musical roots and various “found” songs that have been refurbished. But do they have to be so humorous? Where’s the dignity?

But I suppose you might actually like all this fun and enthusiasm. If so, you’ll probably be taken in by the first half-dozen tunes: ska beats mixed with Latin beats that alternate with fusions of the two; “1000 kilohertz of heavyweight ska”; spirited vocals; shiny horn charts; a twinkle of calypso. You’ll also fall for the next half-dozen tunes: bounciness as a guiding principle; sound effects that could just as easily be inspired by Spike Jones as by The Upsetter; jazz solos on sax and marimbula; a sing-along vocal; a ska/cumbia fusion; howls and other vocal interjections; complex percussion. And then you’re likely depraved enough to want the last four tunes as well: “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf” chased along in a quick, bumpy ska; “the world’s first ska changüi”, based on a hopelessly old Cuban tune; an instrumental version of one of the most appealing earlier songs; a “dancehall mix” of another. Fortunately, that’s where the CD ends.

So if you feel that rhythmic body movements and unpretentious fun are reasonably acceptable, especially when practically forced out of you by totally inspired musicianship, you should probably buy “Ska Cubano”. Or if you just happen to like life, you should also get it. As for me, I’m dumbfounded.

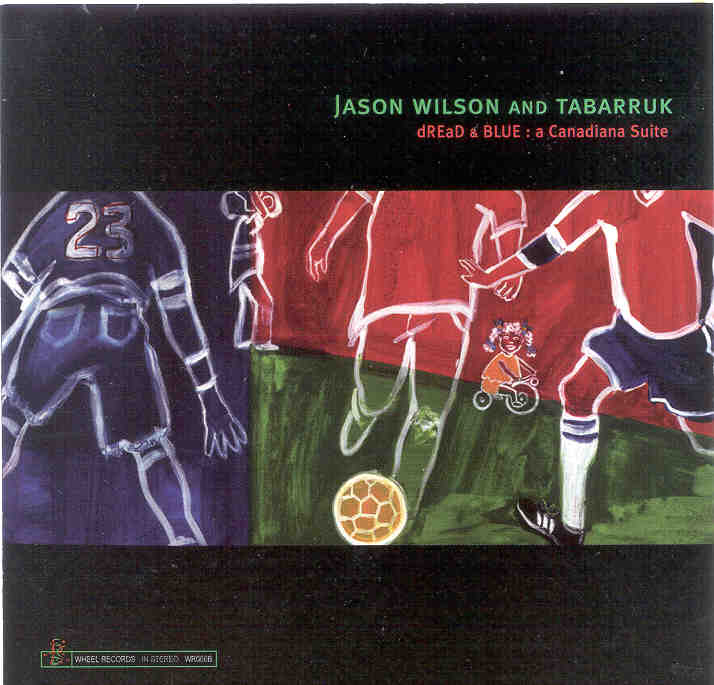

Jason Wilson and Tabarruk: dREaD & BLUE: a Canadiana Suite, Wheel Records, 2004

Jason Wilson and Tabarruk: dREaD & BLUE: a Canadiana Suite, Wheel Records, 2004

This album has an awkward title. I guess it signifies a connection between reggae, jazz and the Canadian identity, but let’s not worry about it. Just be aware that there’s nothing remotely awkward in the tight, harmonious, balanced music contained on the disk inside.

The title suite describes a coming of age in a thoroughly multicultural neighbourhood in a suburb of Toronto. Jason Wilson, the songwriter and lead singer, writes convincingly about his own memories, responses and observations. So although these experiences were far from the ghettos of Jamaica, he is able to explore many of the same “reality” issues of roots reggae—equality, justice, race relations, financial pressures—with his own voice. But is he justified in using reggae rhythms? He sure is; he grew up hearing and loving them. All of which means that he has been able to make a brand of reggae that never falls back on the clichés of the genre, and his music is all the more credible as a result. As for the jazz, well, it’s a fairly mainstream style, but refreshing and adventurous when integrated so naturally into this setting.

In the lead-off track, the gentle sounds of kids at play introduces a piano motif, then a repeated vocal phrase comes in over a strongly grooving rhythm; add a jazz horn arrangement and multitude of textures and suddenly the mix gets very full. Track 3, “The Downsview Shockout”, presents the jazzier side of the equation: piano and saxophone solos played with skill and zest to a propulsive but unhurried rhythm, leaving lots of room for inventive interpretations of the pleasant tune. My favorite, though, has to be “Walk on a Sunday Morning” with its percussive intro, tasty piano, good lyrics (“This ain’t no Kingston 12 but we had our problems still/oh, on that I can be sure…”), strong chorus and upbeat reggae rhythm. “Soon come, Jackie” is, I assume, a tribute to Jackie Mittoo (who moved from Jamaica to Toronto in the mid-70s), although more in spirit than in imitation. As well as spirited horn chart and sometimes Mittoo-like piano, it boasts a rollicking beat to keep things lively and appealing across several flugelhorn, bass and piano solos. Another highlight is “Those Long Winters”, which has a truly Canadian folksiness to the tune, lyrics and mood, with the added benefit of beautiful vocal harmonies that fit perfectly with the quick, insistent reggae backdrop.

The Canadiana suite ends without announcement or fanfare, but there’s still room on the CD for some unique cover versions of songs with Canadian origins: tunes by Messenjah, The Band, Oscar Peterson and Jane Siberry. They form a fitting conclusion to what may have seemed a strange concept: jazzy reggae (or reggeish jazz) via Canada. No, it’s not roots reggae, nor does it pretend to be, but it is a creative expression of a valid artistic vision, well worth both your time and money.

Stitchie: Kingdom Ambassador, Drum & Bass Music, 2004

Stitchie: Kingdom Ambassador, Drum & Bass Music, 2004

Stitchie was once dancehall’s famous Lt. Stitchie, but since then he has been ordained as a minister in Florida. Luckily, a change of life, even a drastic one like becoming a born-again Christian, doesn’t mean rejecting everything, so he is still singing. Sure, he’s preaching now when he does it, and I don’t usually appreciate sung sermons, but in fact I find his approach far less judgmental and self-righteous than other gospel reggae I’ve heard. Granted, there is the part in the liner notes where he quotes from the most extreme parts of the New Testament, condemning various sinners (including liars, so listen up) to “the lake which burns with fire and brimstone.” But when he’s not quoting others, Stitchie seems much more understanding of human nature than people like …well, let’s not mention names.

Fortunately too, Stitchie is a gifted songwriter. Given the genre, his lyrics are surprisingly original explorations of the standard fundamentalist themes, the old standby phrases kept to a relative minimum. Track 1 is a pulsating, energetic beginning: he sounds furious, he absolutely NEEDS to get his message across, naming in a fast-chat deejay style a bunch of his fellow dancehall artists and calling on God to save each. The next song is bouncy, upbeat and catchy; its reassuring message is that country music, R&B, soul, rap, jazz and soca were all created by God. A reworking of Psalm 121 comes next, with a dynamic, full sound and great hook in the chorus. “Are You Ready?” asks us whether we are prepared for the trumpet to blow even if we have business meetings to attend; it’s a fast, no-nonsense treatment with a prominent horn section. “Protective Custody” offers a familiar ska tune and tasty sax solo, while “The Blood” features an infectious handclapping beat that suddenly breaks into fast, full sound. An acoustic guitar ensures that the half-ballad, half-hymn “There’s Hope” is calmer.

That was the first half. The stylistic variety, inventive arrangements, great hooks and convincing singing and chanting continue. “Holy is the Lord” has a wonderful piano intro, gentle vocal, and lyric that includes a line I’ve never heard in reggae before: “to be holy means there is no dichotomy between what you do and what you are.” For another highlight, try the breathy vocal and jazz inflections of “Fresh Vegetable”. By the time he gets to his tribute to “my father, my brother, my pastor, my friend”, sung over a pretty melody on piano, Stitchie has calmed down considerably from his initial pace; he is still intense, just not as excited and single-minded. He closes with a Spanish version of one of the best songs, “More Than Conquerors.”

I haven’t paid too much attention to gospel reggae, but this is the best by far that I’ve heard. If I’m going to be preached at, then please, Lord, let it be by something as dynamic, inventive and appealing as this.

AaVaA: AaVaA, Zip Records, 2004

AaVaA: AaVaA, Zip Records, 2004

This album is self-contradictory. Or is it just finely balanced? It’s power pop—it’s reggae. It’s blatant and body-moving with thump thump drums, muscular guitars, rumbling bass—it’s subtle and intellectual with creative arrangements, skilful performances, interesting lyrics. Effortless and easy skanking—complex and highly structured. These disparate elements often co-exist even within the same song, although luckily the band is too sophisticated to make a big show of it. So the songs flow naturally and nothing sticks out uncomfortably: a rock’n’roll verse merges into a bubbly reggae chorus, a reggae bridge spans rock sections. No matter how radical the change, the alignment is perfect. Maybe the fact that it works so well, so often is thanks to song structures sturdy enough that even the unpredictable can seem inevitable. All that, and the melodies are pretty catchy too.

I love the vocals. They come from Annastasia Victory, a flexible, accomplished singer who can move convincingly from soft and confidential to loud and accusatory within the same song. She can be jazzy, she can be sprightly, she can be Grace Slick at times. And what she sings is often thought-provoking: “Maybe I am just like you/Inconsistencies in everything I do/Spinning all my lies into one truth/Passing alibis from me to you.” In another song: “All of the money/In my soul’s bank has been spent/I just thank God/My soul don’t have to pay no rent.” The words can also be refreshingly direct: “I just wanted to love you, not to be your life.” My only complaint about the lyrics is that the relationship they document is stuck in a rut—there’s no resolution, no progression, no regression over the length of the album. Ahh, well, maybe that’s life.

The singing is often dominant but never overpowering, leaving lots of room in the arrangements for guitar and piano solos and many other interesting bits. Which is not only appropriate, given the skill of those involved, but inevitable, because AñaVañA is a tight, proficient band which has very definitely created this album as a group effort. Yes, there is another blonde-led New York power pop foursome out there that once dabbled in reggae rhythms and which has recently arisen from the great beyond, but forget them; there are similarities for sure, and the newcomers may have learned some lessons from the old, but AñaVañA’s rock-reggae mix is more natural, more spontaneous, more consistent, much preferable. Which brings us to the final contradiction, or balance, inherent in this album: it emulates—it originates. We can live with that.

Revelation: Revelation Book 1, Bass Cat Music, 2004

Revelation: Revelation Book 1, Bass Cat Music, 2004

This album not only contains reggae music, it’s about reggae music. This American band loves the stuff, and it couldn’t be more obvious: the liner notes emphasize the fact, the lyrics return to it again and again, and some specific musical influences (Bob Marley et al) are obvious. One of the songs is entitled “I Love Reggae Music”. They even recruited one of their heroes, Wailers’ alumnus Junior Marvin, to play his guitar. Pretty much the whole album is a tribute to roots reggae. So that’s one reason to buy it. Another is that the songs are terrific, and another is that the lead vocals are among the most expressive and soulful I’ve heard in a long while.

After a brief a cappella intro we immediately get into the strong stuff, as “Revelation” lays down a sticky one-drop beat, piercing lead guitar by Marvin, and passionate singing: “Let there be peace from the north to the south, to the west and to the east; Jah give us strength and Jah give us peace.” Next comes “Babylon Is Burning”, which sounds just as you probably expect. One of the tunes that stays with me for hours is “True Love Is Everlasting”, where gentle drum and organ lead into a poignant vocal by lead singer Caleb Ford; he does a great job with the long but very pretty melody line. That blatant promo for reggae music comes next, complete with introductory horn riff, reverential lyrics (“I bought my first Bob Marley album when I was just twelve years old.”), and brief intrusions into ska, rocksteady and dancehall. I get drawn in every time by the lively horns and percolating beat of “Wicked MC”, which is an ode to Alcapone, Big Youth, U Roy and all those others who chatted at the dancehall “…long before hip-hop was even a word.”

And there are many other highlights: the drumming variations in “Wisdom of Solomon”; the rootsy feel of “Bama Man” and the intensity of its vocal; the bright and refreshing trombone at the end of “Freedom Time”. There’s the Hammond b-3 organ vamping around in the background of “Come Chant” as it sets the stage for Marvin’s fine two-minute lead guitar solo. And finally there’s the hidden tune at the very end of the CD: following two minutes and ten seconds of silence, an instrumental/dub suddenly appears and proceeds to entertain us for another seven minutes.

There we have it. Revelation Book 1. An album whose 13 full tracks turn out to be an even fuller 14. An album whose medium (sweet reggae rhythms) is its message (“I want to hear those sweet reggae rhythms…”) as well as its very reason for existing. Niceness.

Poetz 4 Peace: A Pair of Olive Leaves, Olive Tree Music

Poetz 4 Peace: A Pair of Olive Leaves, Olive Tree Music

Wow. Nothing predictable about this. Most of it is reggae (rootsy or almost so), some is dancehall deejay or hip hop, and some is barely accompanied spoken poetry—but somehow room remains for other musical elements acquired from all over. The album is the product of a bunch of creative types who fortunately weren’t bound by an overly developed sense of convention about what is supposed to go with what. They’re much more concerned with getting their message out, and it’s about peace.

Specifically, A Pair of Olive Leaves is about peace on the politically and militarily divided Mediterranean island of Cyprus—not just as its theme, mind you, but as its very genesis (which is too complicated to get into here). This unique, concrete focus gives the album an immediacy, perhaps even a legitimacy, that more universal appeals for peace cannot command. Which doesn’t mean its lyrics about the stupidity of conflict and about the necessity of peaceful cooperation don’t apply more broadly. It just means they’re concentrated as well as passionate, rationally informed instead of zealously ideological.

And the album is optimistic, in both sound and sense. Consider the way the album starts: after a brief, gentle bouzouki solo comes a calm yet emphatic rap (“That’s how we do it/When we work together”) over upbeat, multi-part background singing and a restrained rhythm track; it’s all relatively unadorned, but there is a catchy little tune to make it both effective and engaging. “Revulsion” is also gentle and low-key, a spoken voice atop synthesizer sounds and a drum beating out a reggae rhythm, while “Funky Tilirka” has a fuller sound, with various vibrant world music elements held in place by very dry percussion. The chanted poem, “Life Could Be so Beautiful”, has a repetitious, chiming East Indian riff as backdrop, parts of it sounding like The Beatles in one of their experimental stages.

For dancehall stylee, try track ten, with its fast, changeable rhythm and unique bouzouki texture. But then stay tuned for something completely different, an internationalist complexity of percussion that fairly zips along—considering the lack of melody or any real substance, it’s loads of fun. One of the CD highlights is the traditional tune that you may recognize from the line “Ain’t gonna study war no more”. It has a lively pace, bouncy reggae beat and great sing-along appeal (in this version the lyrics say, “Gonna lay down my sword and shield/Down by the green line”, a reference to the demarcation line that geographically divides Cyprus). It’s loose, folksy and friendly.

A Pair of Olive Leaves is not a showcase for singing, nor for song-writing. Nonetheless, within these 17 tracks resides lots of good music, featuring unique juxtapositions of voices, instrumentation and musical genres. And the album presents a valuable world view based not on theory and not just on observation but on the experience of human existence on one small, troubled island. No wonder the reggae backdrop works so well in communicating that message.

Ravi: The Afro-Brazilian Project, ARC Music, 2004

Ravi: The Afro-Brazilian Project, ARC Music, 2004

If lounge music can be defined as what people who like lounge music listen to, then The Afro-Brazilian Project probably qualifies. But if the corollary is that lounge music is what people who don’t like lounge music wouldn’t be caught dead listening to, then this ain’t it. Because for me this is approximately ninety percent highly listenable.

It’s mostly the enticing rhythms that are responsible—those and the rich variety of other instrumental sounds that complement, surround, or dance upon that fertile bedrock of beat. The very pleasant tunes, of course, also help a lot. As do the vocals, which add variety, interest and sometimes beauty, despite being relatively sparse. The title of the lead-off track, “21-String Samba”, provides a couple of clues as to what is going on here. The 21 strings refer to the African kora that Ravi plays with great technical and artistic skill. The “samba” part reflects what he does with all that mastery: he plays his own rich version of Brazilian music, its authenticity reflected in the company he keeps. Among the noted Brazilian musicians featured here are singer Marlui Miranda, clarinettist Paulo Moura, harmonica player Guta Menezes and percussionist Robertinho Silva. The overall result is a seamless interweaving of the African texture of the lead instrument within a (mostly) dynamic Brazilian milieu. It’s true that there are several quiet, contemplative moments, particularly in the four-part suite “Amazon Journey”, but most of the rest involves complex rhythms that range from gently lilting to furiously driving. Whatever their position along that continuum, the percussion arrangements remain compelling.

A word about the package. As usual with releases on ARC, a comprehensive booklet is included with text in several languages about the music and the musicians. In this case, the primary liner notes are by Ravi himself, and have the flavor of journal entries—meaning they are not particularly well organized or written (in fact, they fairly scream for an editor’s red pen), but they do convey a sense of immediacy. Ravi’s reminiscences, however, are only part of the story; there are also lyrics for one of the songs, brief notes about each track, and short bios of the artists involved. So I can’t complain much about the package. And I can’t really complain about the music either. It’s entertaining stuff, plausibly loungey or not.

Various: Putumayo Presents Women of Africa, Putumayo World Music, 2004

Various: Putumayo Presents Women of Africa, Putumayo World Music, 2004

Every track here is wonderfully listenable, all A material. So why the B rating? First let’s count how many tracks there are. Hmmm…eight, ten, twelve. Now, how many are already on widely distributed albums? Hmmm, three or four. And how many are from the single country of South Africa? Four. Hello, what’s this, a “radio edit” lasting 2:49? The album closer a teasing 1:29? The whole thing barely over 40 minutes? And this purports to represent the musical output of half the population of the enormous land mass (and people mass) that is Africa? Who’s kidjoing whom?

Which brings us to Angélique and her colleagues. Ms. Kidjo’s track is “Bahia”, from her album Black Ivory Soul; it’s lovely, sort of, zipping along efficiently and melodically, all sheen and ambiance. Cesaria Evora’s godchild, Maria de Barros, does even better with a spirited and accessible Evora-like song about being poor but comfortable. Combining highly appealing tune, vocal quality and rhythm, the sisters-led Madagascar group Tarika sing “Retany” from their long-released and well-received album entitled D. The contribution from Cameroon’s Kaïssa has a very Western delivery and rhythm track; it could almost be an American radio-friendly pop tune except for the non-English language.

The island country of Comoros gives us the singer Nawal; the suppleness and vibrancy of her Arabic-influenced vocal are perfectly matched by an amazing percussion that combines West African talking drum with Indian tabla. Dobet Ghahoré from Ivory Coast deftly handles the tunefulness and complex song structure of “Abiani”. The soulful Souad Massi from Algeria has a folky, acoustic style and voice, and from Burundi we have Khadja Nin’s smooth adaptation of a Stevie Wonder song.

That leaves four South African tracks with their engaging interplay of textures and voices. Judith Sephuma’s lead-off is the typically cheery, mid-tempo treat that you’d expect if you know South African music. Sibongile Khumalo’s track has a wonderful clopping rhythm, while Dorothy Masuka (credited as representing Zimbabwe/South Africa), does her vocalizing over jazzy sax and jazzy piano. The closing brief teaser is by Women of Mambazo: yes, the group was connected to Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and yes, they do a female version of the singing style called iscathamiya.

It doesn’t bother me that this album skips so many great African female singers: Miriam Makeba, the Mahotella Queens, Oumou Sangare, Aster Aweke, Cécile Kayirebwa and Cesaria herself for starters. No, the women on this album are all hugely talented and there’s not one I would want displaced. What does bother me about this CD is that there is so much space for more, and so much justification for using that space. Perhaps the compilers tried their best, but finally had to be satisfied with what’s here. And perhaps we have to be satisfied with the fact that it’s less than satisfying as a result.

Various: Saucy Calypsos Volume One, Ice Music, 2003

Saucy calypsos. That’s almost a tautology, isn’t it. A redundancy; the opposite of a oxymoron. Sauciness has never been far from the juicy, seductive centre (hmm, what does that mean? wink, wink) of the genre since it began. Sure, the coy and cutesy kind can seem plain silly nowadays. On the other hand, it can also be amusing when presented in such enjoyable musical form, and amusing and enjoyable bring us very close to entertaining, which is why I can recommend this particular collection of early tracks by some of the Caribbean’s calypso greats.

Quite aside from the lyrical content, another non-surprise will be the line-up of artists represented here, which includes some royalty (Duke, King Fighter, and the Lords Kitchener and Canary) and several of the Mighty folks (Sparrow, Terror and Bomber). They are assigned a total of 14 tracks between them, some of which are in mono and some in stereo, and all of which have been “digitally remastered from original recordings.” So the sound reproduction is about as good as you’re going to find, given the vintage. Speaking of which, the packaging tells us almost nothing about recording dates, musicians, circumstances or any of the other stuff that people like to know when it comes to historical material. That’s a shame and scandal. But at least the lyrics are there.

Okay, onto those lyrics. They range from sly to bawdy to clever to absurdist. Naughtiness runs rampant, of course—much of the naughtiness also being woefully politically incorrect. A few are almost grotesque from today’s vantage point; they date from an era when “yes” meant “yes”, but “no” meant (to the man) only a somewhat greater challenge; it was a time when a calypsonian could presume to make an amusing little narrative out of a description of a near rape. We hear from a guy happily coercing his wife into prostitution, and we are told about doctors and dentists taking advantage of their patients in totally outrageous ways. Not that everything is so dementedly macho and dated; “60 Million Frenchman” certainly proclaims a sexually liberated message, for example.

It’s all harmless enough, I guess, and the sparkling music is the important thing. Most of the tracks offer a 1950s big band kind of calypso, but even there the arrangements are feisty, with vivid horns, tasty guitar and dynamic percussion. So sure, treat yourself to some sauciness, and don’t dare take it seriously.

——————

Although the closest Ted Boothroyd has come to a personal association with the Caribbean was to have a Trinidadian grandfather, which Ted didn’t really have a lot to do with, he happily took in Harry Belafonte’s calypso hits in the ’50s and became a huge reggae fan in 1969 when Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites” hit big in Canada. Ted has reviewed books on Caribbean music for The Beat, writes album reviews for other periodicals, and co-hosts a reggae and world music radio show in Fredericton, New Brunswick, on Canada’s east coast.

——————

Although the closest Ted Boothroyd has come to a personal association with the Caribbean was to have a Trinidadian grandfather, which Ted didn’t really have a lot to do with, he happily took in Harry Belafonte’s calypso hits in the ’50s and became a huge reggae fan in 1969 when Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites” hit big in Canada. Ted has reviewed books on Caribbean music for The Beat, writes album reviews for other periodicals, and co-hosts a reggae and world music radio show in Fredericton, New Brunswick, on Canada’s east coast.

——————

Although the closest Ted Boothroyd has come to a personal association with the Caribbean was to have a Trinidadian grandfather, which Ted didn’t really have a lot to do with, he happily took in Harry Belafonte’s calypso hits in the ’50s and became a huge reggae fan in 1969 when Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites” hit big in Canada. Ted has reviewed books on Caribbean music for The Beat, writes album reviews for other periodicals, and co-hosts a reggae and world music radio show in Fredericton, New Brunswick, on Canada’s east coast.

——————

Although the closest Ted Boothroyd has come to a personal association with the Caribbean was to have a Trinidadian grandfather, which Ted didn’t really have a lot to do with, he happily took in Harry Belafonte’s calypso hits in the ’50s and became a huge reggae fan in 1969 when Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites” hit big in Canada. Ted has reviewed books on Caribbean music for The Beat, writes album reviews for other periodicals, and co-hosts a reggae and world music radio show in Fredericton, New Brunswick, on Canada’s east coast.