“Who is the biggest headliner on the bill this weekend?” asked a friend of mine at Reggae in the Park.

“Who is the biggest headliner on the bill this weekend?” asked a friend of mine at Reggae in the Park.

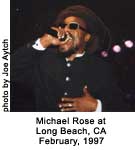

“Probably Michael Rose,” I responded.

“Hmmm… That’s strange. I’ve never heard of him,” she said.

“Remember Black Uhuru?” I asked.

“Ah yes. You mean the band that sings ‘Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner’ and ‘I Love King Selassie’?”

“Exactly. That’s Michael Rose.”

“Wow. That should be great to see.”

Michael Rose may not have penetrated the American mainstream with his name alone–however, his music is recognized from coast to coast. Whether playing in a small club up in Chico, California or a big venue in Miami, Florida, Michael can surely rally the fans (that span at least four decades!) into a frenzy.

This summer was my intensive introduction to Michael Rose. I had seen him perform in years past, but this summer I saw him in concert six times! Let’s see–there was Sierra Nevada World Music Festival, Maritime Hall, Palookaville, Reggae on the Rocks, Reggae in the Park and Brick Works. Needless to say, every show was spectacular and I never got tired of hearing him perform some of Reggae’s greatest hits.

His unique concert attire, black leather from head to toe, is somewhat of an anomaly on the Reggae circuit; however, it fits with Michael’s individuality. It is really a feat when the press is comparing others to you and not the other way around. Michael’s sound is like no other and that in itself is a huge achievement.

I had the opportunity to talk to Michael on July 15, 1999, shortly after his reunion performance with Sly and Robbie at the Sierra Nevada World Music Festival, before his Maritime Hall show. San Francisco was foggy, damp and dark, and Michael seemed a bit melancholic, but he was very forthright about answering my questions.

I entered the room and in plain view, an entire watermelon carcass was perched on the bureau. I thought to myself, “How could anyone eat an entire watermelon?” I think he could see the concern in my eyes and he responded, “I was hungry earlier. I always eat a lot of fruits and vegetables.” With that said, let’s get started…

Having grown up in the Western Kingston ghetto of Waterhouse, Michael got his musical start in Jamaica. Just like Bob Marley, Jacob Miller, Ken Boothe and others, Michael and his brothers began their music by doing the hotel circuit touring as the band Happiness Unlimited.

“The music industry isn’t what it used to be. When I first started out, I had to do the hotel circuit. It wasn’t easy. Do you remember Jimmy Cliff in the movie [“The Harder They Come”] when they keep telling him to come back tomorrow? That happened a lot. Now, it’s a whole different ballgame. It’s not like today when a deejay does a song and it’s in the Billboard and things keep happening. It wasn’t an easy road with the music.”

After leaving Happiness Unlimited in 1975, Michael returned to Kingston where he recorded a number of singles for Niney the Observer and a year later, he took Don Carlos’ place as lead singer for Black Uhuru (alongside Duckie Simpson, Puma Jones, Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare).

With Michael as one of the main songwriters for Black Uhuru, the band really started making waves on an international level, culminating in 1984 with the grand achievement of being the first-ever Grammy Reggae Award recipients for the “Anthem” album (1983).

Michael fondly commented on the days with Black Uhuru, “We were on a journey then. The combination of Puma Jones and Duckie [Simpson], including Sly and Robbie, was good vibes. Black Uhuru made the Guinness Book of Records on that level. For old times sake you just can’t regret things, because it was good then.”

Tired of the constant touring, Michael left Black Uhuru to pursue a solo career, but took a long hiatus to farm coffee in Jamaica’s Blue Mountains, “In Jamaica, lack of employment is very high so I decided to plant some crop and get the youth involved to help them try to do something positive. So, we planted some coffee. They are still doing it now, you know.”

In 1989 he returned to music and signed to RCA, which resulted in the “Proud” album. After his RCA contract was up, he went back to his roots and linked up with Sly and Robbie again, and produced “The Taxi Sessions” in 1995. As a solo artist, Michael has been averaging two albums a year, putting out releases such as “Be Yourself,” “Big Sound Frontline Dubwise,” “Voice of the Ghetto,” “Dance Wicked,” “Dub Wicked,” “Party In Session-Live” and “Nuh Carbon,” a collaboration with Jah Screw, producer who has worked extensively with Barrington Levy.

Touring seemed to be taking a toll on Michael as he explained how difficult it can be sometimes, “The life of the artist is not easy. Everyday you are somewhere else. Sometimes the hotel is good. Sometimes it’s bad and you just have to go along with the [program] because you want to deliver the work and the music is so important. It takes you away from friends, family, everything, but you have to keep on going. If you don’t tour, you don’t sell records. It may look easy, but it’s not easy. A lot of people don’t want to tour, so when you find dedicated people who want to, you have to appreciate it.”

He seems to get a lot of inspiration from the faith he has in Jah, “Jah Rastafari encourages me and makes me strong, so I give utmost credit to Jah.” When I asked him personally what it meant to be a Rasta, Michael replied, “Being a Rasta means to hold your head up high and live clean, try to keep the faith, never lose yourself, read your Bible and pray, because Rasta is a spiritual thing. Once you follow the train of the Father, you can never go wrong.”

Even with all the faith in the world, I thought how difficult it must be to play the same music, day in and day out. In the six performances I attended I heard many of the same tunes: “Short Temper,” “I Love King Selassie,” “Sinsemilla,” “Party In Session,” “Sponji Reggae,” and “Ganja Bonanza.” So I asked him how he could do it over and over. The first point he made was, “After a certain amount of years, you have a new generation who come to the shows. You have to keep pumping the truth and rights in the system.” The second point, and this is more of a character trait, is how much the message means to him, “The music is all about human rights–the upliftment of the people. That is what the music is all about. We try our best. We try to help the youth–less guns, because there are too many youth getting killed by guns.”

He couldn’t tell me which album he was most proud of, “I like them all!” But when I pushed him, he admitted that he is especially proud of “Anthem,” the self-titled “Michael Rose” album and the one that includes “World Is Africa” [Black Uhuru’s “Sinsemilla”]. He has a new release on Heartbeat Records entitled “Bonanza,” a compilation of previously released imports coming out on October 12th. Heartbeat Records execs tell me he has also been recording all new material in Miami for an upcoming release. And to top it off, the 2B1 label is planning to release a live Maritime Hall CD of his July 16, 1999 show. A release date of that one has not been set yet. Well, as he is such a fantastic singer with a unique voice, I am eagerly awaiting all of the new arrivals.

“So, Michael, where do you see yourself in 20 years? Still doing music?”

“We don’t plan for anytime. We just keep working. We just have to take it a day at a time. Rasta don’t plan.” And with that, the interview was over.

“Brilliant,” stated my friend at Reggae in the Park, “Truly brilliant.” And the music spoke for itself.