Calabash Literary Festival 2004

Friday, May 28 – Sunday, May 30

Treasure Beach, Jamaica

![]()

Caribbean literature is very much an international literature, but distill it to the Calabash Festival and there is no longer an international feel, it’s a large village feeling. First of all is the location, a shimmering edge of St. Elizabeth parish, which is, for many consumers of this literature, a faraway place. The classy and eclectic fest, now in its fourth year, is held annually at Jake’s, a world reknown eco-getaway, in Treasure Beach.

Caribbean literature is very much an international literature, but distill it to the Calabash Festival and there is no longer an international feel, it’s a large village feeling. First of all is the location, a shimmering edge of St. Elizabeth parish, which is, for many consumers of this literature, a faraway place. The classy and eclectic fest, now in its fourth year, is held annually at Jake’s, a world reknown eco-getaway, in Treasure Beach.

Second is the scope. About three dozen authors were squeezed into the fourth annual Bash, which began Friday evening with a set of readings by members in the Calabash Writers Workshop and concluded Sunday evening with a panel, “The Kindness of Strangers,” which celebrated random acts of mercy in a variety of global settings.

In between, the program shifted easily across generations and genres and geography.

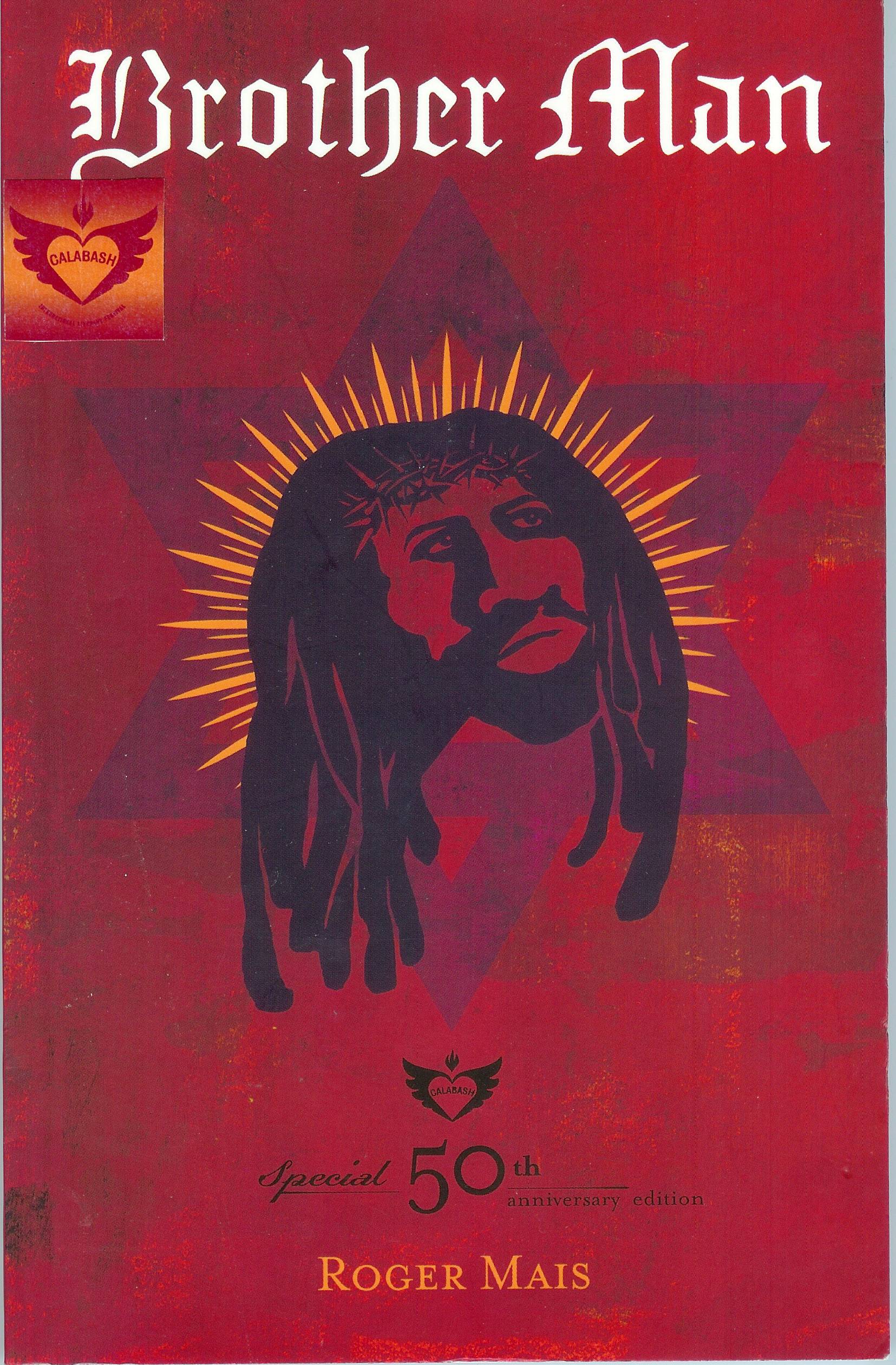

Thus it was that Calabash 2004 incorporated music (a tribute to Peter Tosh, a performance by Ernie Smith), social commentary comedy (Phyllis Stickney) and poetry and fiction of a wide topical and thematic expanse. Authors explored faith (Tessa McWatt: “God is a syllable. Repeated over and over and over until it has meaning.”) and gave parables for the present (Anthony Winkler’s story about a cow in Jamaica neglected by an absentee owner). On Sunday afternoon, the literature moved from distinguished work by Barbadian novelist Austin Clarke, the event’s senior figure, to rolling and tumbling hip hop verse in an open mike session. The poetry of Opal Palmer Adisa, who makes shapely and at times beautifully discomfiting poetry out of the most candid utterances of the female self, also took center stage. A Rasta novel – the first of its kind, Roger Mais’ Brother Man – was launched by Calabash in a reissue edition in partnership with Macmillan-Caribbean.

Thus it was that Calabash 2004 incorporated music (a tribute to Peter Tosh, a performance by Ernie Smith), social commentary comedy (Phyllis Stickney) and poetry and fiction of a wide topical and thematic expanse. Authors explored faith (Tessa McWatt: “God is a syllable. Repeated over and over and over until it has meaning.”) and gave parables for the present (Anthony Winkler’s story about a cow in Jamaica neglected by an absentee owner). On Sunday afternoon, the literature moved from distinguished work by Barbadian novelist Austin Clarke, the event’s senior figure, to rolling and tumbling hip hop verse in an open mike session. The poetry of Opal Palmer Adisa, who makes shapely and at times beautifully discomfiting poetry out of the most candid utterances of the female self, also took center stage. A Rasta novel – the first of its kind, Roger Mais’ Brother Man – was launched by Calabash in a reissue edition in partnership with Macmillan-Caribbean.

While this year’s event was not without glitches (most disappointingly the cancellations of Big Youth, Rita Marley and Indian author Maryse Condé), Calabash can be adjudged a sparkling success. About 2000 people turned out for the weekend, reported Festival Producer Justine Henzell. She, Colin Channer and Kwame Dawes are the prime movers in an organization which in less than half a decade has become the locus for a significant movement in Caribbean letters.

Calabash is, in addition to the principles which animate it, about the atmosphere and ergonomics. Treasure Beach has a small tourist infrastructure in place, but the excesses of tourism found elsewhere on the island are little in evidence. Event-goers are admitted free of charge. The authors and performers read under huge white tents whose tops billow in the gentle breeze, and behind them, south coast waves lap languorously on the shore. (Or not. Sometimes Jamaica’s famous late-May storms hammer the proceedings, as they did in 2002 and 2003.) The sound system is spot-on, with speakers judiciously situated for maximum clarity. On one side of the stage, a bookshop was situated a few steps away; on the other side, good food and a less formal place to gather; in the evenings, a bonfire.

Calabash is, in addition to the principles which animate it, about the atmosphere and ergonomics. Treasure Beach has a small tourist infrastructure in place, but the excesses of tourism found elsewhere on the island are little in evidence. Event-goers are admitted free of charge. The authors and performers read under huge white tents whose tops billow in the gentle breeze, and behind them, south coast waves lap languorously on the shore. (Or not. Sometimes Jamaica’s famous late-May storms hammer the proceedings, as they did in 2002 and 2003.) The sound system is spot-on, with speakers judiciously situated for maximum clarity. On one side of the stage, a bookshop was situated a few steps away; on the other side, good food and a less formal place to gather; in the evenings, a bonfire.

In other words, there are people working very hard here to create a lasting impression, to move mountain and molehill in order to get all the things in place that they, as private readers and academic conference attendees and literary artists themselves, wish to experience. It is a good gig for all, including the authors, who in lieu of stipends receive traveling expenses, lodging and a big, enthusiastically bookish audience with which to perpetrate literature.

Overheard in the little bookshop: While people pored over titles by Calabash authors, a woman held up a paperback to her friend for advice on whether to buy it and was told, “Oh, she can’t write patois.”

Whack!

As criticism goes, the astringency factor ranks up there with a remark that author Tim O’Brien once received about a draft of one of his Vietnam short stories: “It’s not that it’s bad, but you left out Vietnam.”

Indeed, words matter to the Calabash audience. Calabash celebrates the word – scribal and spoken, sung, chanted, chatted and testified. (Indeed, raw testimony is part of the discourse, and in one session of reality programming Ellis Cose probed South Africa’s truth and reconciliation process after apartheid. See related link below.) The spoken word assumes a prominent place in the literature of Caribbean peoples, which leads to a Calabash lesson: While there are anthologies of Caribbean literature (Penguin has one) which split the oral tradition from the scribal by assigning them separate sections, this division is artificial and unreflective of the reality of the people who write and inspire Caribbean literature. Consequently, Calabash mixes and meshes language forms. There is no ism-or-schism in the program or in individual sessions between standard English and patois, or nation language, as Kamau Brathwaite, one of the most influential literary artists of the Caribbean, has called it.

Calabash 2004 was as much about moments as composite effect. From the opening session, the audience proved to be supportive and vocal, not as much as one would find in a church, certainly, but large dollops more than, say, at the annual gathering of the Great Vowel Shift Society.

This is what I mean: Ishion Hutchinson, of the Calabash Writers Workshop, was mid-way through a deeply ruminative erotic poem when he lost his place. He shuffled his manuscript pages, seconds of dead silence ticking away. We were witnessing either the public flustering of an unfortunate wordsmith or else the slick act of someone strategically withholding climax. This appeared to be no contrivance. When he said he must truncate the poem and go on to the next, he was met with loud calls from the audience: “No, manh!” “Finish it, mahn!” In a moment, he did, bringing the poem to the serendipitous concluding line, “I left you in the dream to summon me again.” (My apologies to the poet if line breaks are missing.)

Though Channer says he deplores most “performance poetry” for its histrionics, the three open mike sessions, which were MC’d by professor-author Carolyn Cooper of the University of West Indies-Mona, should have restored his faith in the form. While many of the pieces did operate with performance values up front, the poets, who were limited to three minutes each, maintained a gratifying level of quality. A number of published authors took part as well as amateurs. In particular, a cowboy hat-bearing poet from Indiana dubbed Mental Tattoo endeared himself to the audience with rapid-shot verse about schizophrenic self and society on Friday and Saturday.

Anthony Winkler has lived in Atlanta, Georgia, for a number of years, but if the reception at Treasure Beach this year is any fair measurement of reputation, he is Jamaica’s literary celebrity. When he took to the podium for a Saturday afternoon reading in a showcase of Macmillan-Caribbean writers, he was greeted like a star. The author of The Lunatic and The Painted Canoe, among other works, Winkler read from his new collection of short fiction, The Annihilation of Fish, whose title selection was made into a film starring James Earl Jones and Lynn Redgrave in 1999. He drew laughs with “Absentee Ownership of Cows,” a story in which a cow writes of his “deplorable condition,” and it becomes a wry and a touching parable when, near the conclusion, the narrator observes, “The cow was right. Jamaica gave us life, and what have we given to Jamaica? Our old bones.” When he received a standing ovation, Channer took the microphone and asked Winkler to “lick some more” for the audience, who shouted out “Forward!” and Calabash was obliged with an encore story, “The Dog.”

Behind the Calabashment

Calabash’s mission statement reflects the boldness of its producers, who seek “to transform the literary arts in the Caribbean by being the region’s best-managed producer of workshops, seminars and performances.”

This is no small charge in an island nation where economic pressures eat into leisure time and a budget for books. Emphasizing accessibility to literature is part of the Calabash Master Plan, said Justine Henzell, as well as offering books priced to sell. “The Novelty Ltd. bookstore tries their best to keep prices of books to a minimum for Calabash,” she said, “and many people buy their year’s supply at that time.”

In just its fourth year, Calabash has asserted itself rather vigorously in Jamaica and the diaspora not only as a literature festival but a vehicle for nurturing and showcasing literary talent. Colin Channer, Kwame Dawes and others hosted a series of publishing seminars and writing workshops held in April and May at the University of West Indies-Mona campus, putting them squarely amid apprentice writers and the messiness of questions like “Did you earn that cliché?” and whether a character’s dialogue is believable or a plot device services the overall effect.

In an essay titled “I Am Not in Exile,” Channer explains his commitment: “Almost forty years into independence and our writers—if they have any concern for fairness, time, quality or originality of design—can’t entrust a manuscript to one of OUR publishers. Almost forty years into independence and our readers can’t trust our bookstores to stock our books. Almost forty years into independence and we have not been able to produce and maintain—not just odd examples—but a class of writers who work and live in the region. Who then will tell the stories of the things that a gwaan? About the cruise ships dumping shit on the memories of Mami Wata. About the renta-dreads who bow for the money and make white women feel like lion tamers. About the whole circus that has become our lives” (44).

And what better with which to counteract a circus but a festival. This one appears here to stay. Calabash just added a permanent stage made of concrete, thatch and mosaic tile which rests on a gently sloping hillside on a patch of Jamaican idyll owned by Perry Henzell, known for writing and directing The Harder They Come and has other credits in literature, a roman a clef of 1970s politics and intrigue called Power Game and, more recently, Cane, a historical novel.

Festival producer Justine Henzell, his daughter, is responsible in part for getting the all-important infusions of corporate cash. Channer said as Saturday’s program began, “When Justine goes out and speaks to an Air Jamaica or Bunting and Golding, they’re not listening to Vybz Kartel ‘Tek Money Gal’, you know? Not at all. It is a conversation about business strategy–it is a conversation about the importance of community support and it is a conversation about the importance of supporting the arts.”

Justine Henzell said, “Calabash consumes all my time for three months of the year and most of the time the rest of the year. But it is a team effort, and Colin works equally as hard as I do while writing and touring.”

As one half of the doppelganger behind the programming, founder and artistic director Channer is the author of smartly crafted fiction with overtly sexual appeal for the mass market; he has a new collection of short fiction, Passing Through, set on a fictional Caribbean island. Dawes is a university-based professor and writer of poetry, fiction, drama and criticism; in perpetual literary motion, he has in the last year seen publication of a book about Bob Marley’s song writing (Bob Marley: Lyrical Genius), a collection of short fiction (A Place to Hide) and an anthology of his poetry (New and Selected Poems).

Channer and Dawes are united by a love of representing the broad base of Jamaican cultural life in literature. As Dawes writes in his preface to the reissue edition of Brother Man, “We are making the proposition that books are important to the shaping of a Jamaican culture and that we have, already, a cadre of remarkable authors who have given us splendid models of literature that everyone should be able to enjoy. As Colin Channer has constantly argued, the more we can get Jamaicans excited about reading and enjoying the literature that is about themselves and that understands the values of good, readable literature, the more we are likely to create even greater writers.”

Works Cited

http://www.CalabashFestival.org

Channer, Colin. “I Am Not in Exile.” Obsidian III [Catch Afire: New Jamaican Writing]. Edited by Kwame Dawes. Fall/Winter 2000-2001. 43-55.

Dawes, Kwame. Natural Mysticism: Toward a New Reggae Aesthetic in Caribbean Literature. Leeds, England: Peepal Tree, 1999.

Related Articles

The New Bone to Pick from Ellis Cose

Roger Mais Brother Man: Knotty Dread Steps Forward Again